Why France is at risk of becoming the new sick man of Europe

23 minutes ago

Hugh SchofieldParis correspondent

Hugh SchofieldParis correspondent

BBC

BBCSome people in France were upset to learn this week that their political chaos was being laughed at… by the Italians.

In less than two years France has gone through five prime ministers, a political feat unsurpassed even in Rome’s times of post-war political turbulence.

And now, the French parliament – reconfigured after the president’s decision to hold a snap election in July 2024 – is struggling to produce a majority capable of passing a budget.

Add to this a general strike on Thursday called by unions opposed to previous budget proposals. The strike saw a third of the country’s teachers walk out and most pharmacies shut, with many underground lines in Paris shut too.

Newspapers in Rome and Turin exhibited a distinct gioia maligna (malicious joy) in recounting recent events. There was the humiliation of the recently departed Prime Minister François Bayrou, the warnings of spiralling debt and the prospect of the French economy needing to be bailed out by the IMF.

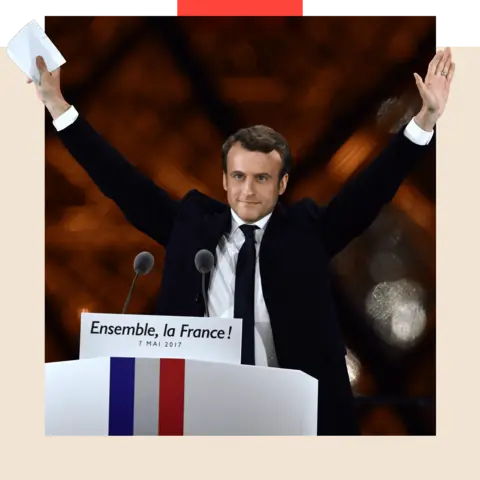

But most of all, there was the fading glory of the president, Emmanuel Macron.

“So where is the grandeur now?” asked Il Messaggero.

LUDOVIC MARIN/AFP via Getty Images

LUDOVIC MARIN/AFP via Getty ImagesThe cost of servicing national debt this year is estimated to be €67 billion – it now consumes more money than all government departments except education and defence.

Forecasts suggest that by the end of the decade it will outstrip even them, reaching €100 billion a year.

Last Friday, the ratings agency Fitch downgraded French debt, potentially making it more expensive for the French government to borrow, reflecting growing doubts about the country’s stability and ability to service that debt.

The possibility of having to turn, cap in hand, to the International Monetary Fund for a loan or to require intervention from the European Central Bank, is no longer fanciful.

And all this against a background of international turmoil: war in Europe, disengagement by the Americans, the inexorable rise of populism.

REUTERS/Tom Nicholson

REUTERS/Tom NicholsonLast Wednesday there was a national day of protest organised by a group called Bloquons Tout (Let’s Block Everything). Hijacked by the far-left, it made little impact bar some high-visibility street clashes.

But a much bigger test came yesterday, with unions and left-wing parties organising mass demonstrations against the government’s plans.

In the words of veteran political commentator Nicolas Baverez: “At this critical moment, when the very sovereignty and freedom of France and Europe are at stake, France finds itself paralysed by chaos, impotence and debt.”

President Macron insists he can extricate the country from the mess but he has just 18 months remaining of his second term.

REUTERS/Benoit Tessier

REUTERS/Benoit TessierOne possibility is that the country’s inherent strengths – its wealth, infrastructure, institutional resilience – will see it through what many feel is a historic turning-point.

But there is another scenario: that it emerges permanently weakened, prey to extremists of left and right, a new sick man of Europe.

Tensions with prime ministers

All of this dates back to Macron’s disastrous dissolution of the National Assembly in the early summer of 2024. Far from producing a stronger basis for governing, the new parliament was now split three ways: centre, left and far-right.

No single group could hope to form a functioning government because the other two would always unite against it.

Michel Barnier and then François Bayrou each staggered through a few months as prime minister, but both fell on the central question that faces all governments: how the state should raise and spend its money.

Bayrou, a 74-year-old centrist, made a totem out of the question of French debt – which now stands at more than €3 trillion, or around 114% of Gross Domestic Product (GDP).

He wanted to stabilise repayments by cutting €44 billion from the 2026 budget.

Bayrou was brought down when the left and far-right MPs united in a vote of confidence last week, but polls showed that many voters were also hostile to the prime minister’s ideas, such as abolishing two national holidays to pay for more defence.

BERTRAND GUAY/AFP via Getty Images

BERTRAND GUAY/AFP via Getty ImagesEmmanuel Macron’s immediate recourse has been to entrust a member of his inner circle to pioneer a new approach.

Sébastien Lecornu, the 39- year-old named as prime minister last week, is a quietly-spoken Norman who became a presidential confidant over late-night sessions of whisky-and-chat at the Elysée.

Following the appointment, Macron said he was convinced “an agreement between the political forces is possible while respecting the convictions of each.”

Macron is said to appreciate Lecornu’s loyalty, and a sense that his prime minister is not obsessed with his own political future.

After tensions with his two predecessors – the veterans Michel Barnier and François Bayrou – today the president and prime minister see eye-to-eye.

“With Lecornu, it basically means that Macron is prime minister,” argues Philippe Aghion, an economist who has advised the president and knows him well.

“Macron and Lecornu are essentially one.”

Lecornu’s Herculean task

Macron wants Lecornu to carry out a shift. From leaning mainly towards the political right, Macron now wants a deal with the left – specifically the Socialist Party (PS).

By law, Lecornu needs to have tabled a budget by mid-October. This must then be passed by year-end.

Arithmetically the only way he can do that is if his centrist bloc is joined by “moderates” to its right and left – in other words the conservative Republicans (LR) and the Socialists (PS).

LUDOVIC MARIN/AFP via Getty Images

LUDOVIC MARIN/AFP via Getty ImagesBut the problem is this: every concession to one side makes it only more likely that the other side will walk out.

For example, the Socialists – who feel the wind in their sails – are demanding a much lower target for debt reduction. They want a tax on ultra-rich entrepreneurs; and an abrogation of Macron’s pension reform of 2023 (which raised the retirement age to 64).

But these ideas are anathema to pro-business Republicans, who have threatened to vote against any budget that includes them.

The main employers’ union MEDEF (Mouvement des Entreprises de France) has even said it will stage its own “mass demonstrations” if Lecornu’s answer to the budget impasse is to raise more taxes.

BENOIT TESSIER/POOL/AFP via Getty Images

BENOIT TESSIER/POOL/AFP via Getty ImagesMaking the situation even more intractable is the timing: the pending departure of Macron makes it all the more unlikely that either side will make concessions. There are important municipal elections in March, and then the presidential elections in May 2027.

At either end of the political checkerboard are powerful parties – the National Rally (RN) on the right, France Unbowed (LFI) on the left – who will be shouting “treason” at the slightest sign of compromise with the centre.

And for any politician of note, there may well be an instinct to limit to the absolute minimum any contact with the fast-eroding asset that is Emmanuel Macron.

Ore Huiying/Bloomberg via Getty Images

Ore Huiying/Bloomberg via Getty ImagesSo Lecornu’s task is Herculean. At best, he might just cobble together a deal and ward off immediate defeat in the Assembly. But such a budget would necessarily be truncated. The signal to the markets would be more French fudge. The cost of servicing debt would rise further.

The alternative is failure, and the resignation of yet another PM.

That way is Macron’s doomsday scenario: another dissolution leading to more elections which Marine Le Pen’s National Rally might win this time.

Or even – as some are demanding – the resignation of Macron himself for his role in presiding over the impasse.

The conjuncture of several crises

Studying France, it is always possible to strike a less “catastrophist” note. After all, the country has been through crises in the past and always muddled through and some see things to admire in Macron’s France.

For the former LR president Jean-Francois Copé, “the fundamentals of the French economy, including its balance of imports and exports, remain solid.

“Our level of unemployment is traditionally higher than the UK’s but nothing disastrous. We have a high level of business creation, and better growth than in Germany.”

Aghion, the former Macron adviser, is also relatively sanguine. “We are not about to go under, Greece-style,” he says. “And what Bayrou said about debt was an effective wake-up call.”

But to others the shifting state of world affairs makes such remarks feel overly optimistic, if not complacent.

Eric COLOMER/Gamma-Rapho via Getty Images

Eric COLOMER/Gamma-Rapho via Getty ImagesAccording to economist Philippe Dessertine, director of the Institute of High Finance in Paris, “we can’t just wave away the hypothesis of IMF intervention, the way the politicians do.

“It is like we are on a dyke. It seems solid enough. Everyone is standing on it, and they keep telling us it’s solid. But underneath the sea is eating away, until one day it all suddenly collapses.

“Sadly, that is what will happen if we continue to do nothing.”

According to Françoise Fressoz of Le Monde newspaper, “We have all become totally addicted to public spending. It’s been the method used by every government for half a century – of left and right – to put out the fires of discontent and buy social peace.

“Everyone can sense now that this system has run its course. We’re at the end of the old welfare state. But no one wants to pay the price or face up to the reforms which need to be made.”

Mustafa Yalcin/Anadolu Agency/Getty Images

Mustafa Yalcin/Anadolu Agency/Getty ImagesWhat is happening in France now is the conjuncture of several crises at once: political, economic, and social – and that is what makes the moment feel so significant.

In the words of pollster Jerome Fourquet last week, “It is like an incomprehensible play being acted out in front of an empty theatre.”

Voters are told that debt is a matter of national life or death, but many either don’t believe it, or can’t see why they should be the ones to pay.

Presiding over it all is a man who came to power in 2017 vested with hope, and promising to bridge the gap between left and right, business and labour, growth and social justice, Euro-sceptics and Euro-enthusiasts.

Following this latest debacle, forthright French commentator Nicolas Baverez drew a devastating conclusion in Le Figaro: “Emmanuel Macron is the real target of the people’s defiance, and he bears entire responsibility for this shipwreck.

“Like all demagogues, he has transformed our country into a field of ruins.”

More from InDepth

BBC InDepth is the home on the website and app for the best analysis, with fresh perspectives that challenge assumptions and deep reporting on the biggest issues of the day. And we showcase thought-provoking content from across BBC Sounds and iPlayer too. You can send us your feedback on the InDepth section by clicking on the button below.