The Skripal poisonings – have British spies learned the lessons?

19 minutes agoGordon CoreraBBC security analyst

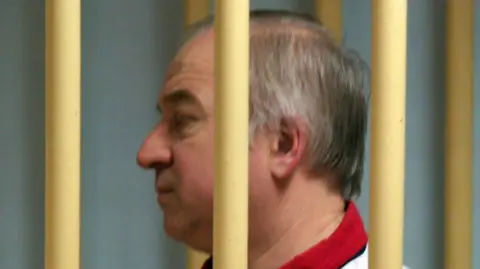

Reuters

ReutersWhen the call came in to the duty officer at MI6 headquarters on the evening of 4 March 2018, it was met with surprise and alarm. One of their agents was lying in a hospital bed, apparently poisoned.

The realisation that Sergei Skripal had been targeted within the UK sent shockwaves through the world of British spies and raised important but difficult questions, some of which have been answered by this latest report. But have all the lessons been learnt?

One question was whether more could have been done to protect Skripal. Skripal had been recruited to spy for MI6 back in the 1990s, but had then been caught by the Russians before being exchanged as part of a spy swap in 2010.

At the time he came to the UK the assessment of the ongoing risk to him had been relatively low. After all, he had been pardoned. This was, top spies later admitted, a mistaken assumption. As a “settled defector” he also had his own say on what kind of security he wanted and he was clear that he did not want a new identity and a new life. That might have been the only thing to prevent the attack.

The report says there may have been nothing to indicate that a dramatic attack using nerve agent might take place, but it does say there were not updated, regular assessments of the risks he faced.

By 2014, the relationship with Russia was darkening thanks to the first crisis over Ukraine. Skripal was also talking to European intelligence services, which may have raised his risk profile. And Russian President Vladimir Putin, a former spy himself, who frequently talks of his hatred for traitors, was not a man to forget betrayal. Nor was the GRU – the Russian military intelligence agency of which Skripal had been a member.

The report suggests the use of Novichok nerve agent was a demonstration of power by the Russian state. But many inside the intelligence world believe what it really was intended to be was a message to others – if they betrayed Russian secrets to Western intelligence, they too would be hunted down even if it took years and even if their family was put at risk.

This lesson was quickly learnt by British intelligence and security services, who immediately after the poisoning placed greater protection around defectors and others at risk in the UK.

AFP via Getty Images

AFP via Getty ImagesThe report says there is no doubt that a unit of the GRU was responsible for the poisoning. They came into the country on a short-term mission and were able to deliver the poison and then leave, abandoning the Novichok-filled perfume bottle that would kill Dawn Sturgess.

The operatives involved were named within months and the wider GRU unit has had many of its operations and some of the fake identities it uses exposed, not least by the investigative site Bellingcat. But could they do it again?

Russian intelligence operations in the UK and Europe have been put under pressure. Following Salisbury and the 2022 invasion of Ukraine, there has been a mass expulsion of Russian diplomats across Europe to make it harder for them to operate. There is more information-sharing to try to detect the travel of operatives as well.

But Russia has also adapted. In recent years, knowing it is harder to get Russian operatives into the UK, it has turned to proxies to carry out its work. For instance, a group of Bulgarians based in the UK were hired from Moscow to carry out surveillance on targets of Moscow for money. They were convicted earlier this year.

They followed people on planes and talked about carrying out kidnappings. They were amateurs but still dangerous. “Of course, they will fail 99% of the time. But the problem is that if they have 100 groups like this, one of this 100 will succeed,” Roman Dobrokhotov, a Russian journalist in exile in the UK and a target of the Bulgarians, told me. “And they don’t care about the 99 groups that will be arrested.”

This is a different model for Russian intelligence – using disposable agents for hire. They have also paid low-level British criminals to carry out arson attacks. This requires a different type of policing in order to be able to spot the activities, compared with the old ways of detecting spies. Counter Terrorism Police say their work to tackle threats from hostile states has grown five-fold since Salisbury.

Today, Russia, its spies and its proxies are engaged in a low-level conflict with the UK and other European countries which involves carrying out acts of surveillance and sabotage. Their ability to carry out another poisoning on a defector using nerve agent is almost certainly diminished thanks to better awareness and stronger defences. But that does not mean there are not other types of danger.