Rift at top of the Taliban: BBC reveals clash of wills behind internet shutdown

50 minutes agoBBC Afghan

AFP via Getty Images

AFP via Getty ImagesIt was a piece of audio obtained by the BBC that revealed what worries the Taliban’s leader most.

Not an external danger, but one from within Afghanistan, which the Taliban seized control of as the previous government collapsed and the US withdrew in 2021.

He warned of “insiders in the government” pitted against each other in the Islamic Emirate the Taliban set up to govern the country.

In the leaked clip, the supreme leader Hibatullah Akhundzada can be heard giving a speech saying that internal disagreements could eventually bring them all down.

“As a result of these divisions, the emirate will collapse and end,” he warned.

AFP / Universal Images Group via Getty

AFP / Universal Images Group via GettyThe speech, made to Taliban members at a madrassa in the southern city of Kandahar in January 2025, was more fuel to the fire of rumours which had been circulating for months – rumours of differences at the very top of the Taliban.

It is a split the Taliban leadership has always denied – including when asked directly by the BBC.

But the rumours prompted the BBC’s Afghan service to begin a year-long investigation into the highly secretive group – conducting more than 100 interviews with current and former members of the Taliban, as well as local sources, experts and former diplomats.

Because of the sensitivity over reporting this story, the BBC has agreed not to identify them for their safety.

Now, for the first time, we have been able to map two distinct groups at the very top of the Taliban – each presenting competing visions for Afghanistan.

One entirely loyal to Akhundzada, who, from his base in Kandahar, is driving the country towards his vision of a strict Islamic Emirate – isolated from the modern world, where religious figures loyal to him control every aspect of society.

And a second, made up of powerful Taliban members largely based in the capital Kabul, advocating for an Afghanistan which – while still following a strict interpretation of Islam – engages with the outside, builds the country’s economy, and even allows girls and women access to an education they are currently denied beyond primary school.

One insider described it as “the Kandahar house versus Kabul”.

But the question was always whether the Kabul group, made up of Taliban cabinet ministers, powerful militants and influential religious scholars commanding the support of thousands of Taliban loyalists, would ever challenge the increasingly authoritarian Akhundzada in any meaningful way, as his speech suggested.

After all, according to the Taliban, Akhundzada is the group’s absolute ruler – a man only accountable to Allah, and not someone to be challenged.

Then came a decision which would see the delicate tug of war between the most powerful men in the country escalate into a clash of wills.

In late September, Akhundzada ordered the internet and phones to be shut off, severing Afghanistan from the rest of the world.

Three days later the internet was back, with no explanation of why.

But what had happened behind the scenes was seismic, say insiders. The Kabul group had acted against Akhundzada’s order and switched the internet back on.

“The Taliban, unlike every other Afghan party or faction, is remarkable for its coherence – there have been no splits, not even much dissent,” explains an expert on Afghanistan, who has been studying the Taliban since they were established.

“Bound into the movement’s DNA is the principle of obedience to one’s superiors, and ultimately to the Amir [Akhundzada]. That’s what made the act of turning the internet back on, against his explicit orders, so unexpected, and so notable,” the expert said.

As one Taliban insider put it: this was nothing short of a rebellion.

A man of faith

Hibatullah Akhundzada did not begin his leadership like this.

Indeed, sources say he was chosen as the Taliban’s supreme leader in 2016 in part because of his approach of building consensus.

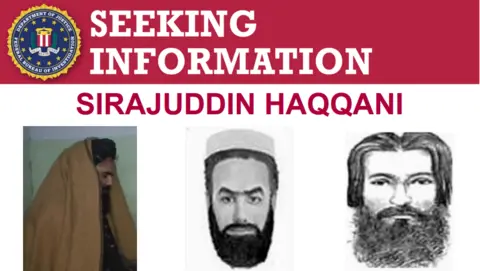

Lacking battlefield experience himself, he found a deputy in Sirajuddin Haqqani – the feared militant commander, then one of the US’s most wanted men with a $10m (£7.4m) bounty on his head.

A second deputy was found in Yaqoob Mujahid, Taliban founder Mullah Omar’s son – young, but bringing with him his Taliban bloodline, and its potential to unify the movement.

The arrangement continued throughout negotiations with Washington in Doha to end the 20-year war between Taliban fighters and US-led forces. The eventual agreement, in 2020, resulted in the sudden and dramatic recapturing of the country by the Taliban, and the chaotic withdrawal of US troops in August 2021.

Los Angeles Times via Getty Images

Los Angeles Times via Getty ImagesTo the outside world, they were a united front.

But both deputies would find themselves quietly demoted to ministers as soon as the Taliban returned to power in August 2021, with Akhundzada now a lone power centre, insiders told the BBC.

Even Abdul Ghani Baradar – the powerful and influential co-founder of the Taliban who had led negotiations with the US – found himself in the role of deputy prime minister instead of prime minister as many had expected.

Instead, Akhundzada – having shunned the capital where the government sits in favour of remaining in Kandahar, a base of power for the Taliban – began surrounding himself with trusted ideologues and hardliners.

Other loyalists were given control of the country’s security forces, religious policies and parts of the economy.

“[Akhundzada], from the outset, sought to form his own strong faction,” a former Taliban member – who later served in Afghanistan’s US-backed government – told the BBC.

“Although he lacked the opportunity at first, once he gained power, he began doing so skilfully, expanding his circle using his authority and position.”

Edicts began to be announced without consultation with Kabul-based Taliban ministers, and with little regard for public promises made before they took power, on issues like allowing girls access to education. The ban on education, along with women working, remains one of the “main sources of tension” between the two groups, a letter from a UN monitoring body to the Security Council noted in December.

Meanwhile, another insider told the BBC that Akhundzada, who had started out as a judge in the Taliban’s Sharia courts of the 1990s, was becoming “even more rigid” in his religious beliefs.

Akhundzada’s ideology was already such that he not only knew but approved of his son’s choice to become a suicide bomber, according to two Taliban officials after his death in 2017.

And he is convinced that making the wrong decision could have implications beyond his lifetime, the BBC has been told.

“Every decision he makes he says: I’m accountable to Allah, on judgement day, I will be questioned why I didn’t take an action,” one current Taliban government official explained.

Two people who have been in meetings with Akhundzada described to the BBC how they were faced with a man who barely spoke, choosing to communicate mainly through gestures, interpreted through a team of elderly clerics in the room.

In more public settings, other eyewitnesses said he obscures his face – covering his eyes with a scarf draped over his turban, and often standing at an angle when addressing an audience. Photographing or filming Akhundzada is forbidden. Only two photos of him are known to exist.

Getting a meeting has also become increasingly difficult. Another Taliban member told the BBC how Akhundzada used to hold “regular consultations”, but now “most Taliban ministers wait for days or weeks”. Another source told the BBC the Kabul-based ministers have been told to “travel to Kandahar only if they receive an official invitation”.

At the same time, Akhundzada was moving key departments to Kandahar – including distribution of weapons, which had previously come under the control of his former deputies Haqqani and Yaqoob.

In its December letter, the UN monitoring team noted Akhundzada’s “consolidation of power has also involved a continued build-up of security forces under the direct control of Kandahar”.

Reports suggest Akhundzada issues direct orders all the way down to local police units – bypassing ministers in Kabul.

One analyst argues the result is that “real authority has been transferred to Kandahar” – something Taliban spokesman Zabihullah Mujahid denied to the BBC.

“All the ministers have their power in their ministerial framework, undertaking daily works and making decisions – all the powers are delegated to them and they carry out their duties,” he said.

However, “from a Sharia perspective, he [Akhundzada] has the absolute power”, Mujahid added – saying “to avoid God-forbidden division, his decisions are final”.

Men ‘who have seen the world’

AP

APAmong the Kabul group, unhappiness was growing and alliances were strengthening.

“They [the Kabul group] are people who have seen the world,” one analyst told the BBC. “Therefore, they believe that their government, in its current form, cannot last.”

The Kabul group want to see an Afghanistan which moves towards the model of a Gulf state.

They are concerned about the concentration of power in Kandahar, the nature and enforcement of virtue laws, how the Taliban should engage with the international community and women’s education and employment.

But despite advocating for Afghan women to have more rights, the Kabul group is not described as moderate.

Instead, insiders see them as “pragmatic”, unofficially led by Baradar – the Taliban founding member who still commands great loyalty. He is also thought to be the “Abdul” referred to by Donald Trump as the “head of the Taliban” during a 2024 US presidential election campaign debate. In fact, he was the group’s chief negotiator with the US.

The Kabul group’s shifting positions have not gone unnoticed.

“We remember that they [the Taliban leaders based in Kabul] used to destroy television sets, but now they appear on TV themselves,” one analyst said.

They also understand the power of social media.

Former deputy Yaqoob – whose father led the Taliban during its first rule, when music and television were banned – finds himself increasingly popular with young Taliban members and some ordinary Afghans, evident in gushing TikTok videos and merchandise adorned with his face.

But no one has been more effective in rebranding themselves than his fellow former deputy, Sirajuddin Haqqani. His ability to evade capture as his network orchestrated some of the most lethal and sophisticated attacks in the Afghan war against US-led forces – including a 2017 truck bombing in Kabul which killed more than 90 civilians near the German embassy – elevated him to near-mythical status among supporters.

During this time, only one known photograph of him existed – taken by a BBC Afghan journalist.

FBI

FBIBut then, six months after the US withdrawal, Haqqani marched out in front of the world’s cameras at a graduation ceremony of police officers in Kabul, his face uncovered.

It was the first step towards a new image: no longer a militant, but a statesman – one with whom the New York Times would sit down in 2024 and ask: is he Afghanistan’s best hope for change?

Just a few months later, the FBI would quietly drop the $10m bounty on his head.

Yet analysts and insiders repeatedly told the BBC that openly moving against supreme leader Akhundzada was unlikely.

Arguably the most visible opposition to his edicts had been minor and limited – for example not enforcing regulations like the ban on shaving beards in regions controlled by Kabul group-aligned officials. But larger acts of rebellion have always been considered unthinkable.

One former Taliban member emphasised to the BBC that “obedience to [Akhundzada] is considered mandatory”.

Haqqani himself, in his interview with the New York Times, played down any chance of an open split. “Unity is important for Afghanistan currently so we can have a peaceful country,” he said.

Instead, one analyst said, the Kabul group is choosing to send “a message to both the international community and Afghans”, one which says: “We are aware of your complaints and concerns, but what can we do?”

At least, that was the case before the order came to shut down the internet.

A breaking point

AFP via Getty Images

AFP via Getty ImagesThe Taliban’s supreme leader is a man with a deep distrust of the internet; he believes its content to be against Islamic teachings, and is so dedicated to his belief that an aide reads out the latest news or social media posts to him each morning instead, his spokesman once explained to the BBC.

The Kabul group believe that a modern country cannot survive without it.

The supreme leader’s internet shutdown order began in provinces controlled by Akhundzada’s allies, before it was expanded to the whole country.

Sources close to the Kabul group and within the Taliban government described what happened next – an almost unprecedented moment in the Taliban’s history.

“It surprised many members of the movement,” one source said.

In short, the Kabul group’s most powerful ministers came together and convinced Kabul-based Prime Minister Mullah Hassan Akhund to order it switched back on.

In fact, the group had already made its unhappiness with the edict known before the internet was cut across the country: the group’s de-facto leader, Baradar, travelled to Kandahar to warn one of Akhundzada’s most loyal governors that they needed to “wake him up” – adding they had to stop being the supreme leader’s “yes” men.

“You don’t tell him the truth openly; whatever he says, you just implement,” he was reported as saying by a Kandahar insider.

His words, the source said, were dismissed. On Monday, 29 September, an order came into the telecommunications ministry directly from the supreme leader to shut everything down. “No excuses” would be accepted, a source in the ministry told the BBC.

On Wednesday morning, a group of Kabul group ministers – including Baradar, Haqqani and Yaqoob – gathered at the prime minister’s office, joined by the telecommunications minister. Here, they urged the Kandahar-aligned prime minister to take charge and reverse the order. According to one source, they told him the full responsibility lay with them.

It worked. The internet returned.

But perhaps more importantly, within those few days, it was as if what Akhundzada had hinted at in that speech months earlier had come to pass: insiders were threatening Taliban unity.

AFP via Getty Images

AFP via Getty ImagesBut why this order? One expert points out Taliban members have been happy to follow Akhundzada despite disagreeing with edicts like the ones on girls’ education.

Meanwhile, many of those who had challenged him openly before had paid a price.

In February 2025, the then-deputy foreign minister had to flee the country after warning publicly the leadership was straying from “the path of God” in “committing injustice against 20 million people” – a reference to the female education ban.

UN monitors point to at least two others who have been arrested after questioning Akhundzada’s decrees on girls’ education, in July and September 2025.

But there is also evidence of Akhundzada and his allies moving to keep figures like Haqqani close – despite the latter’s public criticisms of the supreme leader’s consolidation of power.

Even so, tipping over from words into actions and so decisively disregarding an order was arguably another step all together.

As one expert points out, this time it may have been worth the risk.

Their positions come with power and an “ability to make money”, the expert says. But both depended on the internet, now crucial to both governing and commerce.

“Turning off the internet threatened their privileges in a way that keeping older girls out of education never did,” the expert points out.

“Maybe that’s why they were ‘brave’ that one time.”

AP

APAfter the internet was turned back on, speculation was rife about what would happen next.

A source close to the Kabul group suggested the ministers will be slowly removed or demoted.

However, the Kandahar insider suggested it might be the supreme leader who backed down “because he fears such opposition”.

As the year drew to an end, it appeared publicly that nothing had changed.

The letter to the UN Security Council noted some UN member states “have downplayed the division between leaders in Kandahar and Kabul as akin to a family dispute that would not alter the status quo; all senior leaders are invested in the success of the Taliban enterprise”.

Zabiullah Mujahid, the senior Taliban government spokesman, has categorically denied any split.

“We will never allow ourselves to be divided,” he told the BBC in early January 2026. “All officials and leadership know that a split can be harmful for all, for Afghanistan, religiously prohibited and forbidden by Allah.”

However, he did also acknowledge that differences in “opinion” exist among Taliban members, but equated it to “a difference of opinion in a family”.

Half way through December, those “differences” had appeared to surface once more.

Haqqani was filmed addressing a crowd in his home province of Khost during Friday prayers, warning that anyone who “gets to power through the nation’s trust, love and faith and then abandons or forgets the same nation… is not a government”.

The same day, Akhundzada loyalist Neda Mohammad Nadem – the higher education minister – made his own speech to graduating students at a madrassa in a neighbouring province.

“Only one person leads and the rest follow orders, this is a true Islamic government,” he said. “If there are too many leaders then problems will emerge and this government that we have achieved will be ruined.”

After the dispute over the internet, these recent comments are set against a very different backdrop to those made by Akhundzada in the leaked audio at the start of 2025.

Yet whether 2026 will be the year that the Kabul group move to make meaningful change for the women and men of Afghanistan is very much still up for debate.

“As ever… the question remains after apparent disagreement within the Emirate’s top tier – will words ever lead to action?” says one expert.

“They haven’t yet.”

Edited and produced by Zia Shahreyar, Flora Drury and the BBC Afghan Forensics team. Top image shows two members of the Taliban looking out over Kabul in January 2022.