Number of homeless refugees in England soars, BBC finds

1 hour agoRahil Sheikh,BBC PanoramaandKateryna Pavlyuk,BBC News

Getty Images

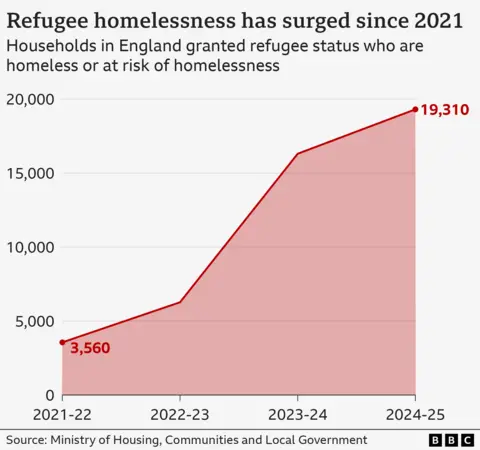

Getty ImagesThere has been a five-fold increase in the number of refugee households who are homeless or at risk of homelessness in the last four years, the BBC has found.

Government data for England showed a rise from 3,560 in 2021/22, to 19,310 in 2024/25.

Charities said the increase was a “direct result” of government policy, and blamed the 28-day period newly-recognised refugees are given to move out of Home Office accommodation – including hotels – as well as faster processing of claims by asylum seekers.

The government said it was “committed” to helping refugees transition from asylum housing to their own accommodation and was working with local authorities “to mitigate the risk of homelessness”.

It comes as successive governments have struggled to get a grip on the UK’s overwhelmed asylum system, with a huge backlog of people waiting for decisions on claims and appeals.

Processing had been slow and, at one point put on pause entirely, but Labour wants to speed up decisions – resulting in more people being granted refugee status and looking for somewhere to live.

One charity supporting homeless refugees said it was mostly seeing young women under the age of 30 asking for help.

Yusra, who arrived in the UK on a small boat after fleeing war in Sudan, is among them. The 26-year-old said her entire family was killed before she arrived in the UK.

She was placed in a government-funded asylum hotel for about five months but said, since she was granted refugee status in late August, she had been sleeping in a tent on the streets of Greater Manchester.

“Sometimes drunk people come and try to open the tent and I start screaming,” Yusra said. “I can’t sleep until the morning.”

In the days before she had to leave her Home Office accommodation, Yusra contacted her local council. However, as a single adult without children, she ranked as low priority for social housing.

Yusra told the BBC she fled Sudan for a better life but now regretted coming to the UK, saying life has been “very difficult” since becoming homeless.

She is one of many refugees receiving support from the Stockport Race Equality Partnership.

Once an asylum seeker is given refugee status they have 28 days to move out of government-funded accommodation – usually a house in multiple occupation (HMO) or a hotel – and find their own housing. At the same time, they must find work or, if necessary, apply for universal credit.

The government has said it usually takes about 35 days to receive an initial universal credit payment. As a result, charities have said many refugees are not able to secure housing or benefits before their asylum support ends.

Jasmine Basran, Head of Policy & Campaigns for national homelessness charity Crisis, said 28 days was not enough time for refugees to sort everything.

She said the charity was seeing the highest rise in homelessness among refugees and the true number without a home was likely to be even higher, as government data only counts those who notify their local authority.

According to the latest figures, London and the North West – including Manchester and Liverpool – have the highest proportion of refugees who are homeless or at risk of homelessness.

The west London borough of Hillingdon saw the sharpest increase – 2,098 homeless households in the area were refugees in 2024/25, up from 71 in 2021/22.

Refugees must seek support from an area they have a local connection to, which is often where their asylum accommodation is. Hillingdon houses a higher number of asylum seekers due to its proximity to Heathrow Airport.

In December, the National Audit Office released a damning report into the asylum system, finding a succession of “short-term, reactive” government policies had moved problems elsewhere, increasing levels of homelessness.

Its criticisms highlighted changes to the 28-day move-on period, a drive to clear inherited asylum backlogs shifting pressure onto appeals, and a shortage of judges creating court backlogs.

Last year, the Labour government ran a pilot increasing the 28-day period for people granted asylum to 56 days, but this ended early, in September, when it reverted back to 28 days.

In 2023, for some refugees, that period shrunk to seven days after the government briefly changed how the move-on period was calculated. The policy was reversed, with the British Red Cross saying it had led to “devastating levels of destitution”.

The 56 day move-on period pilot was, however, extended for those deemed vulnerable – including pregnant women, families with children and disabled people. It was due to end in January 2026, but is understood to still be in place.

It comes as the latest Home Office figures suggest 110,000 people claimed asylum in the year ending September 2025 – a 13% increase on the previous year.

As of September last year, there were 108,085 people in asylum accommodation, with more than 36,000 in hotels and the majority in shared housing, such as HMOs. Asylum accommodation contracts have cost the government billions of pounds.

The government has pledged to clear the backlog of asylum seekers waiting for their claim to be decided, to close “every asylum hotel” and cut asylum costs, adding that “more suitable” sites were being brought forward to “ease pressure on communities”.

But Jacqui Broadhead, director of the Global Exchange on Migration and Diversity at the University of Oxford, said a “long-term reimagining” of asylum policies may be required.

She suggested one solution was to invest in more temporary accommodation instead of paying private providers to oversee asylum accommodation sites such as hotels. After initially being used to help the asylum backlog, she said it could aid the housing shortage more generally.

She highlighted the importance of co-ordination between local authorities and the Home Office, adding that increased and faster decision-making on asylum claims can “put very high levels of pressure” on housing services that are already “extremely stretched”.