How style guru Giorgio Armani revolutionised fashion

6 hours ago

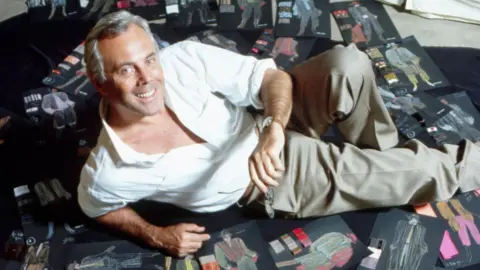

Getty Images

Getty ImagesGiorgio Armani, who has died at the age of 91, was the first designer since Coco Chanel to bring about a lasting change in the way people dress.

Born in a pre-war era of rigid traditions and styles, his creations followed – and helped make possible – increasing social fluidity in the latter half of the 20th Century.

Chiefly, he will be remembered for reinventing the suit – feminising it for men and popularising it for women.

Armani took away the restrictions and confinements of stiffer styles that went before him – making men feel sophisticated and women empowered in the workplace.

Newspapers hailed him the “first post-modern designer”. In many ways, he was a revolutionary.

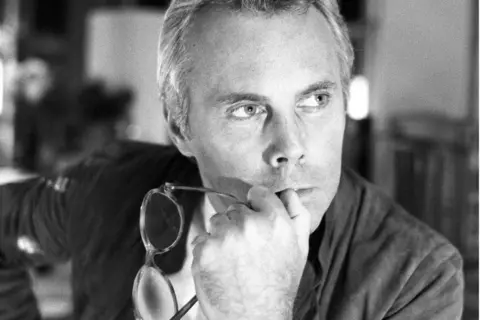

Getty Images

Getty ImagesGiorgio Armani was born in Piacenza, northern Italy, on 11 July 1934.

His family’s comfortable middle-class lifestyle was destroyed by the war and, with food hard to find, his earliest memory was hunger.

Armani played with unexploded artillery shells in the street, until one suddenly went off. He was severely burned and a close friend was killed.

“War,” he later said, “taught me that not everything is glamorous.”

Family photo

Family photoAs a young man, Armani drifted.

In 1956, he began a medicine degree – but dropped out after three years and joined the army.

Swiftly tiring of life in the military, he found a job as a window dresser at La Rinascente – a department store in Milan – where he moved swiftly through the ranks.

Most designers learn their trade as apprentices or at fashion school – but Armani’s education took place on the shop floor.

He learned what fabrics the customers liked, and went to the textile mills to buy them. He became an expert in how the cloth was constructed, and used his knowledge to perfect the tailoring.

Soon, Armani was working for Nino Cerruti – an influential haute couture designer. Within months, Cerruti asked him to restructure the company’s approach.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe 1960s middle classes could not afford haute couture, but yearned for a stylish, distinctive look of their own.

With his expertise in fabrics, Armani provided an answer. His fine cloths made possible a menswear range with neat, precise cuts that could be manufactured at scale.

Its distinctively Italian style began to influence the way the fashionable dressed.

In 1966, Armani met Sergio Galeotti, a young apprentice architect. Galeotti soon abandoned his own career and started to work at his lover’s side.

With immense confidence in Giorgio’s ability, he encouraged Armani to set up on his own.

Galeotti masterminded the business side of the company – and sold his Volkswagen car to raise seed capital.

They started small – their first office was so dingy that Armani took the shades off the lamps in order to see the fabrics. But their work was nothing short of a revolution in fashion.

In broad terms, Armani softened menswear and hardened womenswear.

getty images

getty imagesMen’s suits were made softer and more sensual.

It reflected a change in the way men saw themselves in the 1960s, but it had not yet been captured in fashion.

And with more women entering the workplace, Armani spotted an opportunity.

“I realised that they needed a way to dress that was equivalent to that of men,” he said. “Something that would give them dignity in their work life.”

With Armani’s elegantly tailored power suits, women were offered an alternative to the stiff and stuffy dresses their mothers had worn to work. They exuded femininity, but were a powerful statement of equality.

In 1978, the company signed an agreement with clothes manufacturer GFT – which gave it the ability to produce luxury ready-to-wear clothes in volume.

At the same time, Armani pulled off a huge marketing coup.

He won a contract to dress Richard Gere in American Gigolo. In almost every scene of the 1980 film, Gere’s handsome fantasy-figure form appears head-to-foot in Armani.

Alamy

AlamyIt was Armani’s vision projected by the power of Hollywood – and publicity that money couldn’t buy.

He went on to dress stars on the Oscar night red carpet, and design costumes for dozens of film and television shows: notably The Untouchables and 1980s crime series Miami Vice.

Within a decade, he had become the biggest selling European designer in the United States. As a result, Milan emerged as serious commercial and creative force in world fashion – second only to Paris.

He moved to extend his brand. He launched both Armani Jeans and Emporio Armani – and a deal with L’Oreal added fragrances to his arsenal.

He went on to introduce glasses, sportswear, cosmetics and accessories. Now, there was an entire lifestyle – under one label – to which the fashionable could aspire. GQ magazine described it as the “total look”.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIn 1985, Sergio Galeotti died of an Aids-related illness at the age of 40.

An intensely private man, Armani retreated into himself and considered retirement. Eventually, he decided to persevere rather than “abandon all of Sergio’s hopes”.

Paying tribute to his long-term personal and business partner, Armani said that “he helped me believe in my own work, in my energy”.

In a rare interview in 2001, Armani was asked about the greatest failure of his career. “Not being able to stop my partner dying,” he answered.

With no family to distract him, he dedicated his life to expanding his empire.

While fashion conglomerates bought up other brands, Armani resisted external investment.

Instead, he built the company into the vast global business it is today – and retained control of its finances and creativity. It made him a multi-billionaire.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIn 2000, the Guggenheim Museum in New York hosted an exhibition of his work.

It recognised Armani’s powerful influence on social change in the previous century – and boldly stated that “design could be art”.

He stopped using models with low body mass indexes when one – Ana Carolina Reston – died of anorexia.

Hotel design was added to the portfolio with the opening of the Burj Khalifa in Dubai in 2010. Armani himself designed the interiors.

A keen sports fan, he also designed suits for Chelsea and the England football squad – and made the uniforms for Italy’s Olympic team in 2012.

He had a very public falling-out with US Vogue editor Anna Wintour when she failed to attend the launch of his new season in 2014.

She claimed a diary conflict, but was rumoured to have remarked that “the Armani era is over”.

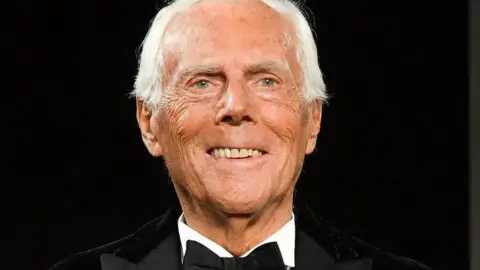

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAs he entered his tenth decade, Armani continued to present new ranges on the catwalks of Paris and Milan.

In March 2025, he said his Milan show aimed to pour oil on the troubled waters of global politics.

“I wanted to imagine new harmony,” he said, “because I believe that is what we all need.”

In person, he was trim and business-like.

New York magazine described him as “notoriously disciplined” and “dedicated to a self-control and self-containedness that can come off as coolness”.

Each morning, Armani would do lengths in his swimming pool. It was 50 yards long but just one yard wide – and contained just enough water to facilitate the laps.

To some, the design of the pool encapsulated the designer’s single-minded approach to life and business. It was minimalist, precise, and engineered for a purpose.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThroughout his career, his styles remained in lockstep with changing society.

The acute sense of social direction came from Armani’s early experience on the shop floor of that Milanese department store.

There, it was the customers who mattered – and a good designer ensured he adapted to their changing needs.

For 65 years, Armani dedicated himself to that task. And it amassed him a fortune estimated by Forbes at $13bn (£10bn).

“I’m never satisfied,” he once told a reporter.

“In fact, as someone who is forever dissatisfied and obsessive in his search for perfection, I never give up until I’ve achieved the results I want.”