Are there more autistic people now?

5 hours agoSimon Maybin & Michael BlastlandThe Autism Curve, Radio 4

Venessa Swaby/Luke Nugent (Luke Nugent Studios)

Venessa Swaby/Luke Nugent (Luke Nugent Studios)There’s a lot at stake. These numbers mean fiercely different things to different people. To some, autism is a fear (what if this happens to my child?); to others it’s an identity, maybe even a superpower.

So what’s the truth about the number of autistic people – and what does it mean?

To count something, you first need to say what it is you’re counting.

For someone to be diagnosed with autism, they need to have “persistent difficulties in social life and in social communication,” says Ginny Russell, an associate professor in psychiatry at University College London (UCL) and the author of The Rise of Autism. She’s using the criteria for autism from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, known as the DSM.

She says examples of this behaviour can range from a lack of turn-taking in conversation to being completely non-verbal.

Restricted interests and repetitive behaviours are part of a second group of traits required to meet the criteria, she says. So things like “hand flapping or rocking or skin picking, but also sticking to repeated routines, like eating the same food every day.”

The data

But what evidence is there that the number of people meeting those criteria has risen?

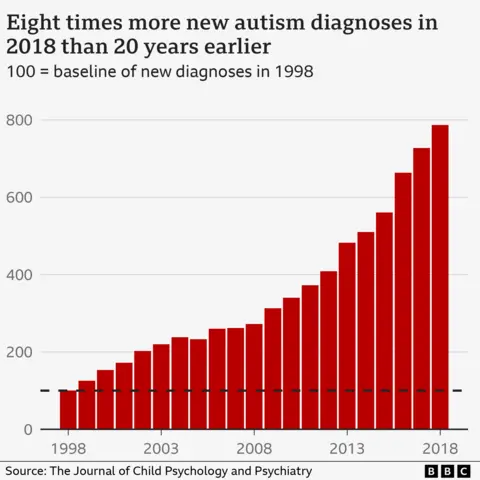

Ms Russell led a study that looked at changes in rates of autism diagnosis in the UK over 20 years. It drew on a big sample of data from about nine million patients who were registered at GP surgeries.

They found eight times as many new autism diagnoses in 2018 as in 1998. “It was an enormous increase,” she says, “best described as exponential.”

And it’s not just happening in the UK. Though data is lacking in much of the world, Ms Russell says that “in the Anglophone and European countries where we do have data, there is compelling evidence to suggest that other countries have seen a similar sort of rise in diagnosis as in the UK”.

But – and this is a crucial point – a rise in the number of people diagnosed with autism is not the same thing as a rise in the number of people who are autistic.

Ms Russell’s study and others like it show there has been a huge rise in the number of people diagnosed with autism, so in that sense there is more autism around than there used to be. But could that rise in diagnosis be explained by changes to who we count as autistic rather than an increase in the number of autistic people?

Why are diagnoses rising?

The definition of autism has not been static. The first studies to describe autism appeared in the 1930s and 1940s, says Francesca Happé, a professor of cognitive neuroscience at King’s College London, who’s been researching autism since 1988.

“The original descriptions of autism are of children who have pretty high support needs, typically are very late to talk,” she says. “Some don’t talk at all. And the focus really was on children, of course, and largely on males.”

But the definition was broadened, Professor Happé says, when in the 1990s Asperger’s syndrome was added to diagnostic manuals. People with Asperger’s were seen as on the autistic spectrum because of social difficulties and repetitive behaviour, but had fluent language and good intelligence, she says.

The eightfold increase in new diagnoses that Ginny Russell found included Asperger’s syndrome, which was seen as a particular type of autism.

Another subset of autism added to the manuals was a “safety net diagnosis” called “pervasive developmental disorder not otherwise specified” (PDD-NOS) and that increased the numbers too.

Today, diagnostic manuals refer simply to autism spectrum disorder, or ASD, which includes people previously diagnosed with Asperger’s or PDD-NOS.

The autism net has been cast wider.

Autism in women and girls

One group of people now falling under this net more often is women and girls.

Studies looking at the huge rise in autism diagnoses show that the rise has been considerably faster for females than for males.

It’s something Sarah Hendrickx has seen in her job as part of a team that diagnoses autism.

“I’ve been doing this maybe 15, 20 years or so,” she says. “In the early days, they were virtually all males that were coming forward for diagnosis. And now they’re nearly all females who I see.”

Ms Hendrickx was herself diagnosed with autism as an adult and is also the author of a book called Women and Girls on the Autism Spectrum.

She says the big growth in the number of people diagnosed with autism is because we’re ”playing catch-up for decades and decades of people like myself”.

Because autism was originally seen as something that affected mainly boys, she says autistic girls would instead be diagnosed with mental health conditions like social anxiety, obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD), and borderline personality disorder (BPD).

Now we have a better understanding of how autism can present in girls and women, thanks to an increase in research and books like Ms Hendrickx’s, which was first published in 2014.

She says that one important gender difference is that girls may be better at masking, which means hiding their autistic traits so that they fit in socially, perhaps by copying others’ behaviour.

More adults diagnosed

The rise in diagnosis has also been much faster among adults than children. Ms Hendrickx says this shows another way the autism net has been cast wider: it now includes more people with lower support needs.

“We are talking, I think, more about individuals with no intellectual disability,” she says. “I think people with delays in their development, in their speech, are much more likely to have been diagnosed much, much earlier because the signs were much clearer at a very young age.”

There’s data to back this up. One study shows that between 2000 and 2018, new autism diagnoses of those with intellectual disability rose about 20%, while autism diagnoses in those without intellectual disability rose 700%. Autism’s centre of gravity has shifted.

For Ellie Middleton, an autistic and ADHD content creator and author, that’s a good thing.

The 27-year-old says that sceptics questioning the increase in diagnoses should instead be asking: “how did all of these people spend so much of their life undiagnosed, unsupported and let down?”

Luke Nugent (Luke Nugent Studio)

Luke Nugent (Luke Nugent Studio)She says she became very mentally unwell before being diagnosed with autism. “I was on the maximum dose of antidepressants that any fully grown adult could be on at the age of 17,” she says. “I couldn’t be left alone, I couldn’t go out.”

Her autism diagnosis three years ago helped her to change the way she lives her life and to keep her mental health in a better place.

But others worry that the version of autism people now see in the media and in their social media feeds is distorting public perceptions.

A focus on celebrities can “glamorise” autism, says Venessa Swaby, who is also autistic and runs support groups for autistic children and their parents through her organisation A2ndvoice. Meanwhile, she says, families with non-speaking autistic children feel they are “written off”.

As the number of people diagnosed with autism has risen, so then has the diversity of autistic people, which, in turn, has brought tensions over who owns the word – and what it means.

Environmental causes

There’s also been a looping effect: as more people are diagnosed with autism, more people become aware of it and that fuels the rise in numbers further.

The internet and social media have played a big part in that – as well as speculation about the reasons behind the rapid rise in diagnoses.

Disproven theories linking the measles, mumps and rubella (MMR) vaccination to autism linger. Others say there must be something in what we eat, drink, or breathe that’s causing more autism.

But, as we’ve seen, the data suggest the rise in diagnoses can be explained by a broadening autism definition rather than an increase in the amount of underlying autism. And there’s solid research showing that autism is largely a product of the genes you inherit from your parents.

Is there any evidence that environmental causes could be playing some part in the rise, even if a small one?

Ginny Russell looked at research into different potential environmental factors and found only a few that were plausible to explain some of the rise.

“There is definitely a quite well established link between autism and the age of the parent,” she says. “If the parent is older you’re more likely to have an autistic child, but it’s not a huge effect.”

She also says that there’s some evidence around “preterm birth and infection during pregnancy and also some birth complications”.

But Ms Russell says it’s important to put those possible factors into perspective.

“I honestly believe that the vast majority of the increase is due to what I would call a diagnostic culture,” she says. “Our conception of the condition has changed, and that’s meant that there’s been an increase.”

You can listen to The Autism Curve on BBC Sounds now