Australia’s universal healthcare is crumbling. Can it be saved?

33 minutes agoTiffanie TurnbullReporting fromStreaky Bay, South Australia

BBC

BBCFrom an office perched on the scalloped edge of the continent, Victoria Bradley jokes that she has the most beautiful doctor’s practice in Australia.

Outside her window, farmland rolls into rocky coastline, hemming a glasslike bay striped with turquoise and populated by showboating dolphins.

Home to about 3,000 people, a few shops, two roundabouts and a tiny hospital, Streaky Bay is an idyllic beach town.

For Dr Bradley, though, it is anything but. The area’s sole, permanent doctor, she spent years essentially on call 24/7.

Running the hospital and the general practitioner (GP) clinic, life was a never-ending game of catch up. She’d do rounds at the wards before, after and in between regular appointments. Even on good days, lunch breaks were often a pipe dream. On bad days, a hospital emergency would blow up her already punishing schedule.

Burnt out, two years ago she quit – and the thread holding together the remnants of the town’s healthcare system snapped.

Streaky Bay is at the forefront of a national crisis: inadequate government funding is exacerbating a shortage of critical healthcare workers like Dr Bradley; wait times are ballooning; doctors are beginning to write their own rules on fees, and costs to patients are skyrocketing.

A once-revered universal healthcare system is crumbling at every level, sometimes barely getting by on the sheer willpower of doctors and local communities.

As a result, more and more Australians, regardless of where they live, are delaying or going without the care they need.

Health has become a defining issue for voters ahead of the nation’s election on 3 May, with both of Australia’s major parties promising billions of dollars in additional funding.

But experts say the solutions being offered up are band-aid fixes, while what is needed are sweeping changes to the way the system is funded – reform for which there has so far been a lack of political will.

Australians tell the BBC the country is at a crossroads, and needs to decide if universal healthcare is worth saving.

The cracks in a ‘national treasure’

Healthcare was the last thing on Renee Elliott’s mind when she moved to Streaky Bay – until the 40-year-old found a cancerous lump in her breast in 2019, and another one four years later.

Seeing a local GP was the least of her problems. With the expertise and treatment she needed only available in Adelaide, about 500km away, Mrs Elliott has spent hundreds of hours and tens of thousands of dollars accessing life-saving care, all while raising three boys and running a business.

Though she has since clawed back a chunk of the cost through government schemes, it made an already harrowing time that much more draining: financially, emotionally and physically.

“You’re trying to get better… but having to juggle all that as well. It was very tricky.”

When Australia’s modern health system was born four decades ago – underpinned by a public insurance scheme called Medicare – it was supposed to guarantee affordable and accessible high-quality care to people like Mrs Elliott as “a basic right”.

Health funding here is complex and shared between states and federal governments. But the scheme essentially meant Australians could present their bright green Medicare member card at a doctor’s office or hospital, and Canberra would be sent a bill. It paid through rebates funded by taxes.

Patients would either receive “bulk billed” – completely free – care, mostly through the emerging public system, or heavily subsidised treatment through a private healthcare sector offering more benefits and choice to those who wanted them.

Medicare became a national treasure almost instantly. It was hoped this set up would combine the best parts of the UK’s National Health Service and the best of the United States’ system.

Fast forward 40 years and many in the industry say we’re on track to end up with the worst of both.

There is no denying that healthcare in Australia is still miles ahead of much of the world, particularly when it comes to emergency care.

But the core of the crisis and key to this election is GP services, or primary care, largely offered by private clinics. There has historically been little need for public ones, with most GPs choosing to accept Medicare rebates as full payment.

That is increasingly uncommon though, with doctors saying those allowances haven’t kept up with the true cost of delivering care. At the same time, staff shortages, which persist despite efforts to recruit from overseas, create a scarcity that only drives up prices further.

According to government data, about 30% of patients must now pay a “gap fee” for a regular doctor’s appointment – on average A$40 (£19.25; $25.55) out of pocket.

But experts suspect the true figure is higher: it’s skewed by seniors and children, who tend to visit doctors more often and still enjoy mostly bulk-billed appointments. Plus there’s a growing cohort of patients not captured by statistics, who simply don’t go to the doctor because of escalating fees.

Brisbane electrician Callum Bailey is one of them.

“Mum or my partner will pester and pester and pester… [but] I’m such a big ‘I’ll just suffer in silence’ person because it’s very expensive.”

And every dollar counts right now, the 25-year-old says: “At my age, I probably should be in my prime looking for housing… [but] even grocery shopping is nuts.

“[I] just can’t keep up.”

This is a tale James Gillespie kept hearing.

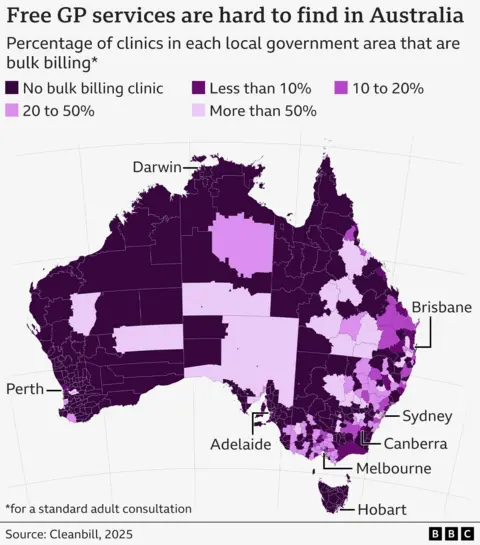

So his startup Cleanbill began asking the question: if the average Australian adult walked into a GP clinic, could they get a free, standard appointment?

This year, they called almost all of the nation’s estimated 7,000 GP clinics – only a fifth of them would bulk bill a new adult patient. In the entire state of Tasmania, for example, they couldn’t find a single one.

The results resonate with many Australians, he says: “It really brought it home to them that, ‘Okay, it’s not just us. This is happening nationwide’.”

And that’s just primary care.

Public specialists are so rare and so overwhelmed – with wait times often far beyond safe levels – that most patients are funnelled toward exorbitantly expensive private care. The same goes for a lot of non-emergency hospital treatments or dental work.

There are currently no caps on how much private specialists, dentists or hospitals can charge and neither private health insurance nor slim Medicare rebates reliably offer substantial relief.

Priced out of care

The BBC spoke to people across the country who say the increasing cost of healthcare had left them relying on charities for food, avoiding dental care for almost a decade, or emptying their retirement savings to fund treatment.

Others are borrowing from their parents, taking out pay-day loans to buy medication, remortgaging their houses, or selling their possessions.

Kimberley Grima regularly lies awake at night, calculating which of her three children – who, like her, all have chronic illnesses – can see their specialists. Her own overdue health checks and tests are barely an afterthought.

ABC News/Billy Cooper

ABC News/Billy Cooper“They’re decisions that you really don’t want to have to make,” the Aboriginal woman from New South Wales tells the BBC.

“But when push comes to shove and you haven’t got the money… you’ve got no other option. It’s heart-breaking.”

Another woman tells the BBC that had she been able to afford timely appointments, her multiple sclerosis, a degenerative neurological disease, would have been identified, and slowed, quicker.

“I was so disabled by the time I got a diagnosis,” she says.

The people missing out tend to be the ones who need it the most, experts say.

“We have much more care in healthier, wealthier parts of Australia than in poorer, sicker parts of Australia,” Peter Breadon, from the Grattan Institute think tank says.

All of this creates a vicious cycle which feeds even more pressure back into an overwhelmed system, while entrenching disadvantage and fuelling distrust.

Every single one of those issues is more acute in the regions.

Streaky Bay has long farewelled the concept of affordable healthcare, fighting instead to preserve access to any at all.

It’s why Dr Bradley lasted only three months after quitting before “guilt” drove her back to the practice.

“There’s a connection that goes beyond just being the GP… You are part of the community.

“I felt that I’d let [them] down. Which was why I couldn’t just let go.”

She came back to a far more sustainable three-day week in the GP clinic, with Streaky Bay forced to wage a bidding war with other desperate regions for pricey, fly-in-fly-out doctors to fill in the gaps.

It’s yet another line on the tab for a town which has already invested so much of its own money into propping up a healthcare system supposed to be funded by state and private investment.

“We don’t want a gold service, but what we want is an equitable service,” says Penny Williams, who helps run the community body which owns the GP practice.

When the clinic was on the verge of closure, the town desperately rallied to buy it. When it was struggling again, the local council diverted funding from other areas to top up its coffers. And even still most standard patients – unless they are seniors or children – fork out about A$50 per appointment.

It means locals are paying for their care three times over, Ms Williams says: through their Medicare taxes, council rates, and then out-of-pocket gap fees.

Who should foot the bill?

“No-one would say this is the Australia that we want, surely,” Elizabeth Deveny, from the Consumers Health Forum of Australia, tells the BBC.

Like many wealthy countries, the nation is struggling to cope with a growing population which is, on average, getting older and sicker.

There’s a small but increasing cohort which says it is time to let go of the notion of universal healthcare, as we’ve known it.

Many doctors, a handful of economists, and some conservative politicians have sought to redefine Medicare as a “safety net” for the nation’s most vulnerable rather than as a scheme for all.

Health economist Yuting Zhang argues free healthcare and universal healthcare are different things.

The taxes the government collects for Medicare are already nowhere near enough to support the system, she says, and the country either needs to have some tough conversations about how it will find additional funds, or accept reasonable fees for those who can afford them.

“There’s always a trade-off… You have limited resources, you have to think about how to use them effectively and efficiently.”

The original promise of Medicare has been “undermined by decades of neglect”, the Australian Medical Association’s Danielle McMullen says, and most Australians now accept they need to contribute to their own care.

She says freezes to Medicare rebates – which were overseen by both parties between 2013 and 2017 and meant the payments didn’t even keep up with inflation – were the last straw. Since then, many doctors have been dipping into their own pockets to help those in need.

Both the Labor Party and the Liberal-National coalition accept there is a crisis, but blame each other for it.

Opposition leader Peter Dutton says his government will invest A$9bn in health, including funds for extra subsided mental health appointments and for regional universities training key workers.

“Health has become another victim of Labor’s cost of living crisis… we know it has literally never been harder or more expensive to see a GP than it is right now,” health spokesperson Anne Ruston told the BBC in a statement.

On the other side, Albanese – whipping out his Medicare card almost daily – has sought to remind voters that Labor created the beloved system, while pointing out the Coalition’s previously mixed support of the universal scheme and the spending cuts Dutton proposed as Health Minister a decade ago.

“At this election, this little card here, your Medicare card, is what is at stake,” Albanese has said.

His government has started fixing things already, he argues, and has pledged an extra A$8.5bn for training more GPs, building additional public clinics, and subsidising more medicines.

ABC News/Billy Cooper

ABC News/Billy CooperBut the headline of their rescue packages is an increase to Medicare rebates and bigger bonuses for doctors who bulk bill.

Proposed by Labor, then matched by the Coalition, the changes will make it possible for 9 out of 10 Australians to see a GP for free, the parties claim.

One Tasmanian doctor tells the BBC it is just a “good election sound bite”. He and many other clinicians say the extra money is still not enough, particularly for the longer consults more and more patients are seeking for complex issues.

Labor has little patience for those criticisms, citing research which they claim shows their proposal will leave the bulk of doctors better off and accusing them of wanting investment “without strings attached”.

But many of the patients the BBC spoke to are sceptical either parties’ proposals will make a huge difference.

There’s far more they need to be doing, they say, rattling off a wish list: more work on training and retaining rural doctors; effective regulation of private fees and more investment in public specialist clinics; universal bulk billing of children for all medical and dental expenses; more funding for allied health and prevention.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesExperts like Mr Breadon say, above all else, the way Medicare pays clinicians needs to be overhauled to keep healthcare access genuinely universal.

That is, the government needs to stop paying doctors a set amount per appointment, and give them a budget based on how large and sick the populations they serve are – that is something several recent reviews have said.

And the longer governments wait to invest in these reforms, the more they’re going to cost.

“The stars may be aligning now… It is time for these changes, and delaying them would be really dangerous,” Mr Breadon says.

In Streaky Bay though, locals like Ms Williams wonder if it’s too late. Things are already dangerous here.

“Maybe that’s the cynic in me,” she says, shaking her head.

“The definition of universal is everyone gets the same, but we know that’s not true already.”

More on Australia election 2025HealthcareAustralia