Brigitte Bardot: The blonde bombshell who revolutionised cinema in the 1950s

17 minutes agoSam Woodhouse

Hulton Archive/Getty Images

Hulton Archive/Getty ImagesBrigitte Bardot, who has died at the age of 91, swept away cinema’s staid 1950s’ portrayal of women – coming to personify a new age of sexual liberation.

On screen, she was a French cocktail of kittenish charm and continental sensuality. One publication called her “the princess of pout and the countess of come hither”, but it was an image she grew to loathe.

Ruthlessly marketed as a hedonistic sex symbol, Bardot was frustrated in her ambition to become a serious actress. Eventually, she abandoned her career to campaign for animal welfare.

Years later, her reputation was damaged when she made homophobic slurs and was fined multiple times for inciting racial hatred. Her son also sued her for emotional damage after she said she would have preferred to “give birth to a little dog”.

It was a scar on the memory of an icon, who – in her prime – put the bikini, female desire, and French cinema on the map.

Lido/Shutterstock

Lido/ShutterstockBrigitte Anne-Marie Bardot was born in Paris on 28 September 1934.

She and her sister, Marie-Jeanne, grew up in a luxurious apartment in the plushest district of the city.

Her Catholic parents were wealthy and pious, and demanded high standards of their children.

The girls’ friendships were closely policed. When they broke their parent’s favourite vase, they were whipped as a punishment.

Roger Viollet via Getty Images

Roger Viollet via Getty ImagesWith German troops occupying Paris during World War II, Bardot spent most of her time at home, dancing to records.

Her mother encouraged her interest and enrolled her in ballet classes from the age of seven.

Her teacher at the Paris Conservatoire described her as an outstanding pupil, and she went on to win awards.

Life as a ‘jeune fille’

But Bardot found life claustrophobic. By the age of 15, she later recalled, “I was seeking something, perhaps a fulfilment of myself.”

A family friend persuaded her to pose for the cover of Elle, the leading women’s magazine in France, and the photographs caused a sensation.

Bettmann Archive/Getty Images

Bettmann Archive/Getty ImagesAt the time, fashionable women had short hair, carefully matched their accessories, and sported tailored jackets and silky evening wear.

Brigitte’s hair flowed around her shoulders. With the lithe, athletic body of the ballerina, she was nothing like her fellow models.

Pictured in a series of young, modish outfits, she became the personification of a new “jeune fille” (young girl) style.

At the age of 16, she found herself the most famous cover girl in Paris.

Her pictures caught the attention of the film director Marc Allegret, who instructed his assistant, Roger Vadim, to track her down.

QUINIO/Gamma-Rapho via Getty Images

QUINIO/Gamma-Rapho via Getty ImagesThe screen tests were not successful, but Vadim – who was six years older – took her on, first as his protégé and then as his fiancée.

They began an intense affair, but when Bardot’s parents found out, they threatened to send her away to England.

S.N. Pathe Cinema/Getty Images

S.N. Pathe Cinema/Getty ImagesRoger Vadim, her ‘wild wolf’

In retaliation, she attempted to take her own life, but was discovered and stopped just in time.

Brigitte was infatuated with the aspiring director.

He seemed to her as a “wild wolf”.

“He looked at me, scared me, attracted me, and I didn’t know where I was anymore,” she later explained.

Hulton Archive/Getty Images

Hulton Archive/Getty ImagesUnder such pressure, her parents relented, but forbade the couple from marrying until Brigitte was 18.

As soon as that milestone was passed, the couple walked down the aisle.

Becoming an icon

Vadim began to mould Bardot into the star that he believed she could be.

He sold the pictures of their wedding to Paris-Match and instructed her in how to perform in public.

He helped his new wife find small roles in a dozen minor films, often playing pouty-yet-innocent female love interests.

But, until 1956, she was chiefly famous for posing in bikinis – until then a garment banned in Spain, Italy and much of America for being on the razor edge of decency – and popularising a beehive hairdo.

Then came peroxide, and the part that made her a star.

That year, Vadim’s debut film, And God Created Woman, opened in Paris. It failed to make money in France, but caused uproar in the United States.

Marka/Universal Images Group via Getty Images

Marka/Universal Images Group via Getty ImagesIn a country used to Doris Day, Bardot was a sensation.

Her character pursues her sexual appetites, without shame, as men do. She dances barefoot in a trance, her skin glowing with sweat, with her hair worn wild and loose.

Her lack of inhibition causes social order to collapse; outside the cinema, the reaction was just as intense.

The existentialist Simone de Beauvoir hailed her as an icon of “absolute freedom” – raising Brigitte to the status of a philosophy.

But the American moral majority mobilised. The film was banned in some states, and newspapers denounced its depravity.

To audiences, Bardot became indistinguishable from the character she played. Paris-Match branded her “immoral from head to toe”.

And when Bardot ran off with her co-star, Jean-Louis Trintignant, her image as a wanton libertine was inescapable.

Atlantis Films/Pictorial Parade/Courtesy of Getty Images

Atlantis Films/Pictorial Parade/Courtesy of Getty ImagesShe divorced Vadim, who reacted as only a Frenchman could.

“I prefer to have that kind of wife,” he said, “knowing she is unfaithful, rather than possess a woman who just loved me and no-one else.”

He went on to work with Bardot again, and later live with Catherine Deneuve and marry Jane Fonda.

A reluctant mother

In 1959, Brigitte – after several love affairs – married the actor Jacques Charrier, with whom she starred in Babette Goes To War.

The couple had a son, Nicolas, but Bardot resented her pregnancy: repeatedly punching herself in the stomach and begging a doctor for morphine to induce a miscarriage.

“I looked at my flat, slender belly in the mirror like a dear friend upon whom I was about to close a coffin lid,” she later recalled.

AFP via Getty Images

AFP via Getty ImagesAfter the inevitable divorce, Nicolas did not see his mother for decades.

He sued Bardot for emotional damage when she published an autobiography in which she stated that she would have preferred to “give birth to a little dog”.

Brigitte was now the highest paid actress in France, with some suggesting that she was more valuable in terms of foreign trade than the country’s car industry.

But she wanted to be taken seriously as an actress. “I have not had very much chance to act,” she complained, “mostly I have had to undress.”

She began to attract the attention of Europe’s most respected film-makers, winning critical acclaim in Jean-Luc Godard’s powerful, New Wave drama, Le Mépris (Contempt).

But the overall quality of her output was mixed, especially when she ventured outside France and into Hollywood.

A third marriage, to a millionaire German playboy, was followed by a string of lovers – although, uncharacteristically, she did reject Sean Connery.

Bettmann Archive/Getty Images

Bettmann Archive/Getty ImagesShe made dozens of records, alongside Serge Gainsbourg and Sacha Distel.

With Gainsbourg, she recorded the raunchy Je T’aime… Moi Non Plus, although she begged him not to release it.

A year later, he re-recorded the song with the British actress, Jane Birkin. It became a huge hit all over Europe, with Bardot’s version remaining under wraps for 20 years.

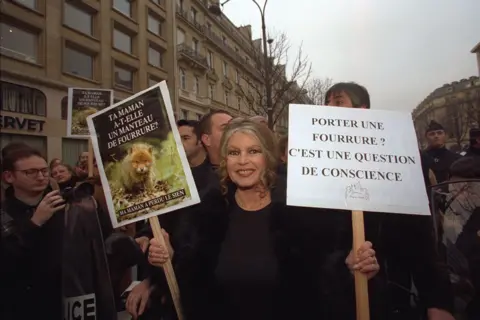

Animal rights campaigner

After nearly 50 films, she announced she was retiring to devote her life to animal welfare in 1973.

“I gave my beauty and my youth to men”, she said. “I’m going to give my wisdom and experience to animals”.

Philippe Caron/Sygma/Getty Images

Philippe Caron/Sygma/Getty ImagesShe raised 3m francs (then about £300,000) to establish the Brigitte Bardot Foundation, by auctioning off her jewellery and film memorabilia.

Bardot – or B.B. as she was known in France – campaigned against the annual seal cull in Canada, and irritated some of her countrymen by condemning the eating of horse meat.

She became a vegetarian, attacked the Chinese government for “torturing” bears, and spent hundreds of thousands on a programme to sterilise Romanian stray dogs.

Sygma via Getty Images

Sygma via Getty ImagesA troubled end to a troubled life

In her later years, she was prosecuted on multiple occasions for racial hatred.

She objected to the way the Islamic and Jewish faiths slaughter animals for food.

But the way she voiced her criticism was unforgivable, and – indeed – illegal.

In 1999, she wrote that “my homeland is invaded by an overpopulation of foreigners, especially Muslims”. This landed Bardot with a huge fine.

She went on to criticise interracial marriages and insult gay men who, in her words, “jiggle their bottoms, put their little fingers in the air, and with their little castrato voices moan about what those ghastly heteros put them through”.

Bardot was in court so often that, in 2008, the prosecutor declared that he was “weary” of charging her.

Gilles BASSIGNAC/Gamma-Rapho via Getty Images

Gilles BASSIGNAC/Gamma-Rapho via Getty ImagesIn the 1960s, Brigitte Bardot was chosen as the official face of Marianne, the emblem of French liberty.

Then she herself became an icon: a beautiful, liberated, modern woman who refused to conform to outdated stereotypes.

After three failed marriages and several suicide attempts, she gave up the spotlight to campaign against cruelty to animals. To her surprise, the media’s fascination with her continued, even as fame became notoriety.

She is survived by her fourth husband Bernard d’Ormale, a former adviser to the late far-right politician Jean-Marie Le Pen.

And, in a troubled end to a troubled life, Bardot’s political opinions meant she spent her final years as a semi-recluse fighting race-hate allegations in the courts.