Could RFK Jr’s move to pull mRNA vaccine funding be a huge miscalculation?

1 hour agoJames GallagherHealth and science correspondent•@JamesTGallagher

Getty Images

Getty ImagesmRNA vaccines were heralded as a medical marvel that saved lives during the Covid pandemic, but now the US is pulling back from researching them.

US Health Secretary Robert F Kennedy Jr has cancelled 22 projects – worth $500m (£376m) in funding – for tackling infections such as Covid and flu.

So does Kennedy – probably the country’s most famous vaccine sceptic – have a point, or is he making a monumental miscalculation?

Prof Adam Finn, vaccine researcher at the University of Bristol, says “it’s a bit of both” but ditching mRNA technology is “stupid” and potentially a “catastrophic error”.

Let’s unpick why.

Kennedy says he has reviewed the science on mRNA vaccines, concluding that the “data show these vaccines fail to protect effectively against upper respiratory infections like COVID and flu”.

Instead, he says, he would shift funding to “safer, broader vaccine platforms that remain effective even as viruses mutate”.

So are mRNA vaccines safe? Are they effective? Would other vaccine technologies be better?

And another question is where should mRNA vaccines fit into the pantheon of other vaccine technologies – because there are many:

- Inactivated vaccines use the original virus or bacterium, kill it, and use that to train the immune system – such as the annual flu shot

- Attenuated vaccines do not kill the infectious agent, but make it weaker so it causes a mild infection – such as the MMR (measles, mumps and rubella) vaccine

- Conjugate vaccines use bits of protein or sugar from a bug, so it triggers an immune response without causing an infection – like for types of meningitis

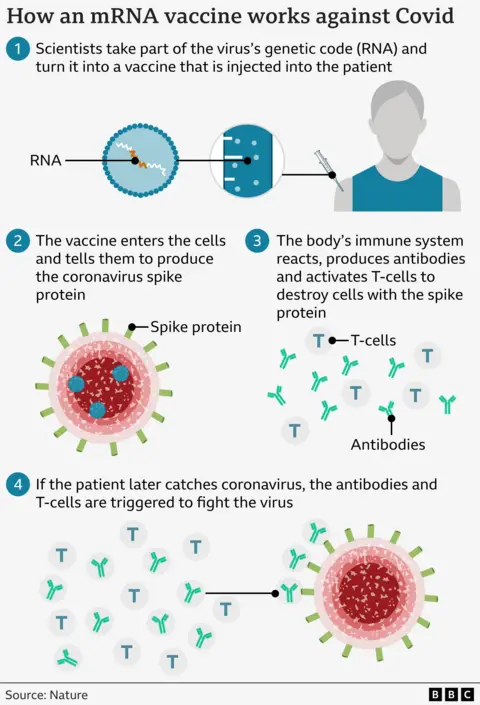

- mRNA vaccines use a fragment of genetic code that temporarily instructs the body to make parts of a virus, and the immune system reacts to that

Each has advantages and disadvantages, but Prof Finn argues we “overhyped” mRNA vaccines during the pandemic to the exclusion of other approaches, and now there is a process of adjusting.

“But to swing the pendulum so far that mRNA is useless and has no value and should not be developed or understood better is equally stupid, it did do remarkable things,” he says.

Do mRNA vaccines work?

The claim that mRNA vaccines do not protect against upper respiratory infections like Covid and flu “just isn’t true”, says Prof Andrew Pollard from the Oxford Vaccine Group, who is soon stepping down as the head of the Joint Committee on Vaccination and Immunisation (JCVI), which advises the UK government.

The vaccines were shown to provide protection – keeping people alive and out of hospital – in both clinical trials and then during intense monitoring of how the vaccines performed when they were rolled out around the world.

In the first year of vaccination during the Covid pandemic, it was estimated that the Pfizer/BioNTech mRNA vaccine alone saved nearly 6 million lives.

Against that there were a small number of cases of inflammation of heart tissue – called myocarditis – particularly in young men.

“Very rare side effects should be balanced against the huge benefit of the technology,” says Prof Pollard.

The pandemic was an era when the world was single-mindedly focused on Covid and the rollout of vaccines was monitored intensely. The consensus opinion remains they did overwhelmingly more good than harm.

But that does not mean they are a perfect technology.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe mRNA Covid vaccines train the immune system to target just one protein out of the whole virus. If that protein in the coronavirus changes or mutates then the body’s protection is lessened.

We have seen the consequences of that – immunity wanes and the vaccines need to be updated.

One theoretical argument is that a different vaccine approach – such as using the whole virus – would give better protection, as the immune system would have more to target.

However, Prof Pollard says the mRNA vaccines performed better than the inactivated ones when tackling Covid.

He says that is probably down to the way they are made – and the fact that the process of killing the virus also “changes the viral proteins so there is less stimulation of the immune system” in comparison with mRNA vaccines.

The need to update vaccines is not a failing of mRNA technology that can be easily solved by pivoting from one technology to another – instead, it is down to the fundamental nature of some viruses.

The same measles or HPV (human papilloma virus) vaccines have been effective for decades and show no sign of failing as the virus’s genetic codes are more stable in each case.

But some viruses live in a perpetual state of flux.

Flu, for example, is not one virus – but instead a constantly-shifting target. At any time, one strain will be in the ascendancy and be the most likely to cause trouble in winter.

In flu, the inactivated flu injection that is given to adults is updated every year – as is the live vaccine that is given to children as a nasal spray. A future mRNA form of flu vaccine would work the same way.

“The point about keeping up with variants is about all technologies, not just mRNA,” says Prof Pollard.

mRNA is ‘streets ahead’ when speed is needed

There is a legitimate scientific question about which vaccine technology is used for which disease.

What is causing concern among scientists is that pulling mRNA research means we will not have those vaccines at times when we need to do what no other technology can.

Prof Pollard says: “I don’t think there’s the evidence they are hugely better for protection, but where RNA tech is streets ahead of everything else is responding to outbreaks.”

The world is highly drilled at making new flu vaccines each year. But even then, there is a six-month process of deciding on the new flu strains to be targeted, growing the vaccine at scale in chicken eggs and then distributing it. Brand new vaccines take even longer.

But with mRNA, you can have the new vaccine in six to eight weeks, and then tens or hundreds of millions of doses a few months later.

Some of the projects that have had their funding pulled in the US were preparing for a bird flu pandemic. That virus, H5N1, has been devastating bird populations and jumping into a wide range of other animals including American cattle.

“That doesn’t make sense and if we do get a human pandemic of bird flu it could be seen as a catastrophic error,” says Prof Finn.

But the ramifications of the US turning away from mRNA research could be felt more widely.

What impact does this move have on confidence in the current vaccines, mRNA or otherwise? How does it affect the world when the US is one of the most influential countries in medical research? And will it have a knock-on impact on other types of mRNA technology, such as cancer vaccines – or using the approach to treat rare genetic diseases?

Prof Pollard poses another question after RFK Jr’s move: “Does it put us all at risk if a huge market is turning its back on RNA?

“It is one of the most important technologies we’ll see this century in infectious disease, biotherapeutic agents for rare disease and critically for cancer. It’s a message I’m troubled about.”