Sanctions-busting shadow ships are increasing – the big question is what to do about them

43 minutes agoPaul Adams,Diplomatic CorrespondentandKayleen Devlin,BBC Verify

BBC

BBCOn 26 January, staff in an office in Mumbai received an urgent e-mail from a crew member aboard a tanker off the coast of Singapore.

The email, purportedly written on behalf of five colleagues aboard the tanker sailing under the name Beeta, contained a litany of complaints: crew members, it was alleged, had not been paid and were being treated “like animals”; and provisions were running low.

The staff in Mumbai worked for the International Transport Workers Federation (ITF), the world’s leading organisation representing seafarers, and were used to dealing with complaints from all corners of the globe.

But what caught their eye was the fact that the emails hadn’t just been copied to multiple ITF offices, but also to sanctions enforcement bodies in several countries.

“The vessel is sanctioned and blacklisted,” the sailor wrote.

He said he had discovered that the vessel calling itself the Beeta was in fact an American-sanctioned tanker called the Gale.

The sailor and his colleagues were desperate to leave.

“I’ve been at sea for many years,” he told the BBC when we contacted him. “I know what’s right and wrong.”

Inadvertently, the crew member had found himself involved in a problem at the heart of some of today’s most contentious geopolitical issues: a surging number of tankers, transporting Russian and Iranian oil, operating outside maritime rules, using a variety of methods to conceal their identities.

This “shadow fleet”, as it’s known, is growing fast.

ITF

ITFEstimates vary, but the latest data from the monitoring group TankerTrackers.com says the fleet currently consists of 1,468 vessels, roughly triple its size at the time of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine four years ago.

That’s about 18-19% of the total internationally trading tanker fleet, carrying approximately 17% of all seaborne crude, says Michelle Wiese Bockman, senior maritime intelligence analyst at Windward AI.

The phenomenon that first emerged in the 2010s, as North Korea and Iran sought to evade international sanctions, has proliferated, leaving western governments scrambling to keep up.

So what can those governments do when countries circumvent or flout the rules to export oil and use the profits to fuel engines of war or repression?

‘Modern-day slavery’

Definitions vary – as do names: it’s also been called the “dark” or “ghost” fleet – but shadow vessels generally exhibit some or all of a particular set of characteristics.

They tend to be old, averaging an age of around 20 years, and are often poorly maintained. Details of ownership and management are deliberately opaque – names, identification numbers and flags are frequently changed. Insurance is below Western standards and sometimes fake.

Vessels frequently switch off or manipulate their automatic identification system (AIS), making them harder to track.

Seamen, recruited on contracts that typically last six to nine months, don’t always know what they’re getting into.

“I didn’t understand what shadow fleet vessels actually were,” Russian engineer Denis told us, after serving aboard an EU- and UK-sanctioned tanker, Serena, for several months last year.

Serena is currently flying under the flag of Cameroon. While Denis was aboard, it was flying a false Gambian flag.

Denis says he realised the Serena was under sanctions only when he went aboard. But like many seamen, he says he needed the work.

“Once they’re at sea, they’ve got them prisoner on board,” says Nathan Smith, an ITF inspector familiar with the Serena.

Smith has heard numerous stories of abuses aboard shadow vessels.

“It’s a modern-day slavery,” he says.

Over the course of months spent sailing between Russia and China, the reality of life aboard a shadow vessel became increasingly apparent to Denis.

“Things began to deteriorate very quickly because no spare parts were sent,” he said. “The radar on the bridge hadn’t been working for over a year, the life-saving equipment wasn’t working and there were numerous faulty fire sensors.”

During a stop at the Russian port of Vladivostok, last October, the crew tried, without success, to repair a davit, a small specialised crane used to lower the tanker’s life boats into the water. Denis says a port official nevertheless issued a certificate of successful inspection. The BBC has approached the Port of Vladivostok for comment.

Denis says he never found out who owned the Serena or who crew members could contact to raise complaints.

It’s notoriously difficult to establish ownership of shadow fleet vessels. Ships have registered owners, which are often shell companies or entities set up to manage a single vessel. The names of real, or “beneficial” owners are frequently hidden. We have tried to make contact with the owners of the Gale and Serena, but without success. In the case of the Gale, it has proved impossible to establish the identity of the beneficial owner.

Crews are poorly protected throughout the industry, with unpaid wages and abandonment by owners all-too frequent. But Denis says shadow vessels are the worst.

“Now I’ll be more careful,” he says. “I’ve learned to identify dangerous vessels that I won’t work on any more.”

The ships brought back from the dead

Deep within the murky recesses of the shadow fleet also lurks a category experts have dubbed “zombie ships” – vessels which steal the identity of dead ships in order to hide their true identity.

After being sanctioned, a zombie ship often disappears from tracking systems, later reappearing under a new name, using a stolen nine-digit International Maritime Organisation (IMO) number from a scrapped or decommissioned vessel.

The ship’s AIS tracking system, which uses transponders to continuously broadcast its location, is re-programmed to imitate the previous vessel.

With the dead tanker’s identity magically resurrected, the zombie ship continues to ply its trade, free from sanctions.

The Gale is one such ship.

According to the global trade intelligence company Kpler, the tanker, currently flying a false Gambian flag, has assumed multiple identities since being sanctioned by the US last year for its involvement in the export of sanctioned Iranian oil.

After a period sailing under the false identity Sea Shell, using a different stolen IMO number, the Gale again changed identities, re-emerging as Beeta and loading a cargo of Iranian oil on 31 January.

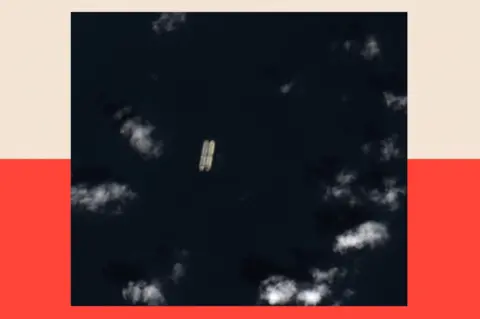

According to TankerTrackers.com, which uses satellite imagery, AIS data and shoreline photography to follow the movement of crude oil, the shipment was delivered by another US-sanctioned vessel via a ship-to-ship transfer, a procedure commonly used by shadow-fleet vessels involved in the shipment of sanctioned oil.

Copernicus Sentinel 2, 2026

Copernicus Sentinel 2, 2026The ship-to-ship transfer took place south of the Riau Archipelago, around 150 miles east of Singapore.

Windward AI’s Michelle Wiese Bockmann calls the area “an epicentre of maritime lawlessness”, where dozens of tankers gather to store or transfer Iranian oil.

Bockmann says China imported 1.8 million barrels per day of sanctioned Iranian crude per day in 2025. The BBC has contacted the Chinese embassy for a response.

“None of it was traced,” she says, “because tankers hide their loading and the oil has come on four or five tankers, deliberately to obscure the origin and destination of the cargo.”

The Gale’s history and behaviour mark it out as a classic zombie ship.

A computer screenshot taken on board by the crew member who contacted the ITF appears to give instructions on how to fake the ship’s location, a process known as spoofing.

Two other screenshots, taken on 26 January, show the spoofing at work.

One displays the tanker’s actual location, east of Singapore. The second, taken just five minutes later, shows a fake location, around 2,800 miles away, off the coast of the Indian state of Gujarat.

“The confirmed linkage between Gale, Sea Shell, and Beeta, alongside fabricated AIS position history and prior impersonation, is consistent with deliberate identity manipulation,” says Ana Subasic, an analyst at the global trade intelligence company Kpler.

The BBC has no reason to believe the Serena is a zombie vessel, but the ship’s former engineer says he saw equipment that would enable the Serena to fake its position.

“I spoke with the bridge officers about turning off the AIS and other manipulation,” Denis told us. “We had equipment on board to change the vessel’s position. I think this equipment is only used for sanctioned cargo.”

What can be done?

Such practices, coupled with the knowledge that Russian and Iranian oil revenues continue to fuel conflict in Ukraine and the Middle East, are driving an urgent debate in western capitals about how to respond.

Donald Trump’s recent actions in Venezuela – seizing seven tankers since early December as part of a pressure campaign on the regime of then president Nicolás Maduro – has shown that one solution is the simple application of force.

The operation to chase and capture one vessel, the Russian-flagged tanker Marinera, took the US military, including a coastguard vessel and special forces, on a two-week chase far out into the North Atlantic.

The Marinera, previously known as the Guyanese-flagged Bella 1, was wanted by the US for transporting sanctioned oil from both Venezuela and Iran.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe change of name and flag was designed to provide the tanker with a measure of international protection.

Upping the ante further, Russia took the highly unusual step of requesting that the US call off its pursuit and said it had dispatched a submarine to escort the tanker, which was empty at the time. The Russian Foreign Ministry said there was not “any basis” to allege the tanker was sailing “without a flag” or “under a false flag”.

Undeterred by the possibility of an international incident or by the possible accusation of piracy on the high seas, the US intercepted the Marinera in international waters between Iceland and the UK in the early hours of 7 January.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesFor the first time, the UK got involved, sending an RAF surveillance aircraft and a Royal Navy support ship to help the operation.

Defence Secretary John Healey said the action was “in full compliance with international law” and said the UK was “stepping up activity against shadow vessels”.

Perhaps spurred on by Washington’s assertive approach, there is some evidence that European partners are willing to take more robust action too.

Two weeks after the Marinera episode, France launched an operation in the Mediterranean to seize the Grinch, another Russia-linked tanker suspected of violating international sanctions.

Reuters

ReutersOnce again, the UK was involved. A Royal Navy patrol boat, HMS Dagger, shadowed the Grinch, as it passed through the Strait of Gibraltar.

With at least one sanctioned vessel passing through the English Channel every day, according to experts, speculation is mounting that the UK might soon conduct its own interceptions.

Healey recently told MPs that “further military options” were being explored.

For some, it can’t come soon enough.

“There’s obviously huge frustration in the policy-maker circles in Brussels and London that Russia is continuing to sell its oil,” says Tom Keatinge, founding director of the Centre for Finance and Security at the Royal United Services Institute (Rusi) in London.

Keatinge runs a maritime sanctions task force at Rusi, bringing together representatives from industry and government. Some participants, he sees, are keen to see more forthright action.

“We have people… who like jumping out of helicopters on ropes,” he says. “And that community has thus far been kept firmly in its box.”

He adds: “Put bluntly, no one’s had the balls to look at what is often a 50-50 call and say ‘We’ll send the boys in’.” The MoD said: “Deterring, disrupting and degrading the Russian shadow fleet is a priority for this government.”

But the constraints are considerable.

“You’ve got a bunch of consequences that you need to be ready to deal with,” Keatinge says. “The first is you’ve got an absolutely enormous vessel. What the hell do you do with that?”

Once seized, tankers need to be maintained, with engines running and a skeleton crew on board. The appetite for holding such vessels, particularly older ones that might pose an environmental risk, is minimal.

The Marinera remains moored in the Moray Firth, with other US-seized vessels being held off the coast of Texas and Puerto Rico.

“If you look at the very high costs that the US is probably incurring at the moment to have two tankers off Houston, awaiting legal action, it’s not something you take lightly,” says Bockmann.

A problem of resources

Then there’s the question of what to do with the oil itself.

Again, Trump’s approach is blunt: confiscate it.

The president says 50 million barrels have been taken so far, as the US assumes control of Venezuela’s oil industry.

“Venezuela is going to get some and we’re going to get some,” he said in a recent interview.

The president’s European allies are unlikely to follow suit.

“That would probably be a step too far for the Foreign Office,” says Keatinge.

So would Ukraine’s increasingly direct approach. In recent months, Kyiv has targeted at least seven Russian shadow fleet tankers, using a variety of drones and mines.

Reuters

ReutersMost of Ukraine’s attacks have been in the Black Sea, but one tanker, the Qendil, was hit and critically damaged while passing through the Mediterranean in December. Another tanker, the Mersin, was attacked and immobilised off the coast of Senegal in late November. Kyiv has not commented on reports that it carried out the attack.

Most of the international effort so far has been more bureaucratic than kinetic: sanctioning hundreds of vessels, persuading countries such as The Gambia, Sierra Leone and Comoros, among others, to tighten their regulations, and addressing the issue of insurance.

The number of falsely flagged ships globally more than doubled last year to over 450, according to the IMO, the BBC reported in November.

Last year, the European Commission introduced new rules requiring all vessels entering EU waters to provide proof of insurance.

The UK has a similar, voluntary reporting scheme, but shadow fleet vessels often ignore it or alter course when challenged.

Ultimately, the sheer number of shadow vessels poses a simple problem of resources.

But with Russian ships sometimes suspected of involvement in the monitoring or sabotage of undersea cables, there’s an added national security dimension.

In late January, the UK and thirteen other countries with Baltic and North Sea coastlines issued a coordinated warning that AIS manipulation, along with interference with Global Navigation Satellite Systems represented a growing threat to maritime safety and security.

Vessels sailing under flags of convenience, the statement said, “may be treated as a ship without nationality”, under the terms of the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea, a reminder to anyone paying attention that existing laws already provide for the detention and seizure of ships.

Windward AI’s Bockmann says the Trump administration’s actions over Venezuela have shown European leaders what can be done.

“There’s definitely a low threshold [for intervention] building for the darkest of the dark fleet,” she says.

More from InDepth

The net is gradually closing on Russian oil. Last October, the Trump administration imposed sanctions on the country’s two largest oil companies, Lukoil and Rosneft.

The EU’s next sanctions package against Russia may include a full ban on maritime services, making it impossible for European tankers to transport Russian oil under the legal price cap currently in place.

Around 30% of Russia’s maritime oil exports are currently carried on EU-owned vessels.

But for Russia and Iran, war and sanctions are the mothers of invention. As the net tightens, you can be sure that the world’s burgeoning fleet of shadow vessels will continue to operate in the dark.

Top picture: Getty Images

BBC InDepth is the home on the website and app for the best analysis, with fresh perspectives that challenge assumptions and deep reporting on the biggest issues of the day. Emma Barnett and John Simpson bring their pick of the most thought-provoking deep reads and analysis, every Saturday. Sign up for the newsletter here