Terence Stamp: 1960s icon who was the ‘master of the brooding silence’

6 minutes ago

BBC

BBCTerence Stamp’s dashing good looks and smouldering glare made him a star of 1960s cinema.

One of the stalwarts of Swinging London, the working class actor’s first film earned him an Oscar nomination.

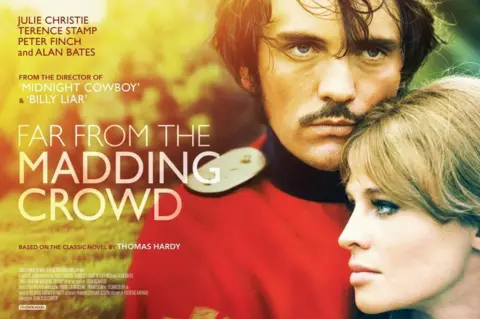

With actress Julie Christie or supermodel Jean Shrimpton on his arm, he specialised in playing sophisticated villains: including Superman’s arch nemesis, General Zod, and the petulant Sergeant Troy in Far From the Madding Crowd.

The Guardian called him the “master of the brooding silence”, but Stamp’s acting proved to have range as well as depth.

Thirty years after his career began, he shocked his fans – but picked up a Golden Globe nomination – as Bernadette Bassenger in The Adventures of Priscilla, Queen of the Desert.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesTerence Henry Stamp was born in Stepney, east London, on 22 July 1938.

His father, a man Stamp once described as “emotionally closed down”, was a ship’s stoker and often away from home.

Young Terence’s interest in acting began to blossom when his mother took him to the local cinema to see Gary Cooper in Beau Geste, a film that left a deep impression on him.

After enduring the Blitz in the east end of London, the Stamp family moved to the more genteel Plaistow – where Terence attended grammar school before getting the first of a series of jobs in advertising agencies.

In his autobiography, Stamp Album, he recalled how he loved the life, but he could not shake off the feeling he wanted to be an actor.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesHaving been turned down for National Service because of problems with his feet, he won a scholarship to the Webber Douglas Academy of Dramatic Art – which got rid of his cockney accent.

After completing his studies, he set out on the grinding local repertory circuit that was the training ground for all aspiring actors in the 1950s.

On one occasion, he found himself in a touring production of The Long and the Short and the Tall alongside another budding actor named Michael Caine, with whom he would later share a flat.

Stamp’s leap to stardom came when he was cast in the title role of a 1962 film, Billy Budd, based on the Herman Melville novella.

His performance as the naïve young seaman, hanged for killing an officer in self-defence, won him an Academy Award nomination for Best Supporting Actor and a Golden Globe for Best Newcomer.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIn the same year, he appeared in Term of Trial alongside Laurence Olivier.

Stamp was hailed as one of the new wave of actors from working-class backgrounds, such as Albert Finney and Tom Courtenay, who were also making a name for themselves.

In 1965, Stamp starred in an adaptation of the John Fowles novel The Collector, as the repressed Frederick Clegg who kidnaps a girl and imprisons her in his cellar.

By now, he was regularly seen at the most fashionable 1960’s gatherings, and his good looks brought him plenty of female attention.

There was a relationship with the actress Julie Christie, who he’d approached after seeing her holding a gun on a magazine cover in 1962.

The affair only lasted a year, but was later immortalised by the Kinks in the song Waterloo Sunset: with a line referencing Terry and Julie crossing over the river.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesHe turned down the chance to star in Alfie, having played the part on stage. His flatmate, Michael Caine, took the role instead and it launched his career.

In 1966, Stamp appeared as Willie Garvin – a rough Cockney diamond – in the film version of Peter O’Donnell’s comic strip, Modesty Blaise.

And, a year later, he starred as a bank-robber-with-a-soft-heart in Ken Loach’s kitchen sink drama, Poor Cow.

Stamp found Loach difficult. The director, he felt, was too political and hid the script from the cast – preferring to feed them lines while shooting each scene.

“Before a take, he’d say something to (co-star Carol White),” he complained, “and then he would say something to me, and we only discovered once the camera was rolling that he’d given us completely different directions.

That’s why he needed two cameras, because he needed the confusion and the spontaneity.”

Getty Images

Getty ImagesHe was reunited with Julie Christie in Far From the Madding Crowd.

He was dating Jean Shrimpton by then, but their on-screen chemistry was still evident.

“On the set, the fact that she had been my girlfriend just never came up,” he told The Guardian in 2015.

“I saw her as Bathsheba, the character she was playing, who all the men in the film fell in love with. But it wasn’t hard, with somebody like Julie.”

With cinematographer Nicholas Roeg, Stamp helped choreograph the famous fencing demonstration scene: in which Sergeant Troy’s sword skills captivate – and eventually seduce – Bathsheba Everdene.

But the film got poor reviews and failed at the box office. And Stamp fell out with the director, John Schlesinger.

“He didn’t strike me as a guy who was particularly interested in film,” the actor recalled. “Plus I wasn’t his first choice: he really wanted Jon Voight.”

Getty Images

Getty ImagesBut Stamp’s star was beginning to fade.

An outing in Blue – a “pretentious, self-conscious, literary Western without much zest”, according to one critic – didn’t help.

He was approached to play James Bond when Sean Connery relinquished the role, but his radical ideas of how he should interpret the character did not impress producer Harry Saltzman.

Stamp suggested that he might start a Bond film disguised as a Japanese warrior – and slowly reveal himself to be 007.

“I think my ideas about it put the frighteners on Harry,” he speculated. “I didn’t get a second call from him.”

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThere was a spell in Italy where he worked with the directors Pier Paolo Pasolini and Federico Fellini but, by the time he returned to London, the 60s were drawing to a close and he was no longer in fashion.

“When the 1960s ended, I just ended with it. I remember my agent telling me: ‘They are all looking for a young Terence Stamp.'” He was still only 31.

Disillusioned, he bought a round-the-world ticket and found himself in India – experimenting with vegetarianism, yoga and living in a spiritual retreat.

It was there, in 1976, that he received a message addressed to ‘Clarence’ Stamp, offering him the part of General Zod in Superman.

Alamy

AlamyWith his leading man days behind him, Stamp discovered that playing villains was liberating.

Superman and the sequel, Superman II, put him firmly back on the public stage – and he appeared in a bewildering variety of genres.

There were Westerns like Young Guns, crime dramas like The Hit and The Real McCoy – and even a gothic thriller in Neil Jordan’s fantasy, The Company of Wolves.

But his most unlikely – and celebrated – performance was as transgender woman in the Australian film, The Adventures of Priscilla, Queen of the Desert in 1994.

Stamp was not keen to do the film – in fact, he thought the initial offer was a joke.

But a female friend persuaded him to take the part – which saw his character journey across the outback with two drag queens, played by Hugo Weaving and Guy Pearce.

“It was a challenge, a challenge I couldn’t resist because otherwise my life would have been a lie”, said Stamp.

Alamy

AlamyOver the next 10 years, Stamp appeared in two dozen films – playing a wide variety of parts.

In 1999, he entered the Star Wars canon: playing a politician battling corruption in Episode I: the Phantom Menace – an experience he later described as “dull”.

More satisfyingly, he starred in The Limey: as a career English criminal hunting for his missing daughter.

A decade later, he was nominated for a Bafta for his role as the grumpy husband of a dying woman in A Song for Marion.

In 2002, he married for the first time at the age of 64.

Stamp had met Elizabeth O’Rourke in a chemist shop in Australia. She was 35 years younger, and the marriage lasted six years.

Getty Images

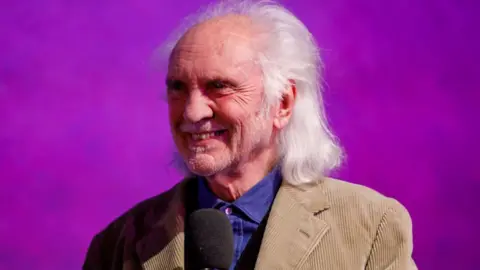

Getty ImagesTerence Stamp continued to act well into his 80s.

The parts – like his fleeting appearance as a silver-haired gentleman in Edgar Wright’s Last Night in Soho in 2021 – grew smaller, although a sequel to Priscilla was in development.

He will be remembered as the actor who blazed like a comet at the height of the 1960s, surrounded by the decade’s most beautiful women.

His career fizzled close to extinction, but he showed an impressive ability to reinvent himself – with his ability to project style and menace bringing him to the attention of new generations.

It was a career that unfolded with no thought of planning, no clear strategy and no goal in mind.

“I don’t have any ambitions,” Stamp once said. “I’m always amazed there’s another job.”

“I’ve done crap, because sometimes I didn’t have the rent. But when I’ve got the rent, I want to do the best I can.”