The race for the two miles-a-second super weapons that Putin says turn targets to dust

20 minutes ago

Frank GardnerSecurity correspondent

Frank GardnerSecurity correspondent

EPA-EFE/KCNA

EPA-EFE/KCNAGlinting in the autumn sun on a parade ground in Beijing, the People’s Liberation Army missiles moved slowly past the crowd on a fleet of giant camouflaged lorries.

Needle-sharp in profile, measuring 11 metres long and weighing 15 tonnes, each bore the letters and numerals: “DF-17”.

China had just unveiled to the world its arsenal of Dongfeng hypersonic missiles.

That was on 1 October 2019 at a National Day parade. The US was already aware that these weapons were in development, but since then China has raced ahead with upgrading them.

Thanks to their speed and manoeuvrability – travelling at more than five times the speed of sound – they are a formidable weapon, so much so that they could change the way wars are fought.

Which is why the global contest over developing them is heating up.

AFP via Getty Images

AFP via Getty Images

Reuters

Reuters“This is just one component of the wider picture of the emerging geopolitical contest that we’re seeing between state actors,” says William Freer, a national security fellow at the Council on Geostrategy think tank.

“[It’s one] we haven’t had since the Cold War.”

Russia, China, the US: a global contest

The Beijing ceremony raised speculation about a possible growing threat posed by China’s advancements in hypersonic technology. Today it leads the field in hypersonic missiles, followed by Russia.

The US, meanwhile, is playing catch-up, while the UK has none.

Mr Freer of the Council on Geostrategy think tank, which received some of its funding from defence industry companies, the Ministry of Defence and others, argues that the reason China and Russia are ahead is relatively simple.

“They decided to invest a lot of money in these programmes quite a few years ago.”

Meanwhile, for much of the first two decades of this century, many Western nations focused on fighting both jihadist-inspired terrorism at home, and counter-insurgency wars overseas.

Back then, the prospect of having to fight a peer-on-peer conflict against a modern, sophisticated adversary seemed a distant one.

Shutterstock

Shutterstock“The net result is that we failed to notice the massive rise of China as a military power,” admitted Sir Alex Younger, soon after retiring as chief of Britain’s Secret Intelligence Service in 2020.

Other nations are also racing ahead: Israel has a hypersonic missile, the Arrow 3, designed to be an interceptor.

Iran has claimed to have hypersonic weapons, and said it launched a hypersonic missile at Israel during their brief but violent 12-day war in June.

(The weapon did indeed travel at extremely high speed but it was not thought to be manoeuvrable enough in flight to class as a true hypersonic).

North Korea, meanwhile, has been working on its own versions since 2021 and claims to have a viable, working weapon (pictured).

The US and UK are now investing in hypersonic missile technology, as are other nations, including France and Japan.

Morteza Nikoubazl/NurPhoto via Getty Images

Morteza Nikoubazl/NurPhoto via Getty ImagesThe US appears to be strengthening its deterrence, and has debuted its “Dark Eagle” hypersonic weapon.

According to the US Department of Defense, the Dark Eagle “brings to mind the power and determination of our country and its Army as it represents the spirit and lethality of the Army and Navy’s hypersonic weapon endeavours”.

But China and Russia are currently far ahead – and according to some experts, this is a potential concern.

Hyper fast and hyper erratic

Hypersonic means something that travels at speeds of Mach 5 or faster. (That’s five times the speed of sound or 3,858 mph.) This puts them in a different league to something that is just supersonic, meaning travelling at above the speed of sound (767 mph).

And their speed is partially the reason that hypersonic missiles are considered such a threat.

The fastest to date is Russian – the Avangard – claimed to be able to reach speeds of Mach 27 (roughly 20,700mph) – although the figure of around Mach 12 (9,200mph) is more often cited, which equates to two-miles-a-second.

In terms of purely destructive power, however, hypersonic missiles are not hugely different from supersonic or subsonic cruise missiles, according to Mr Freer.

“It’s the difficulty in detecting, tracking and intercepting them that really sets them apart.”

There are basically two kinds of hypersonic missile: boost-glide missiles rely on a rocket (like those DF-17 ones in China) to propel them towards and sometimes just above the Earth’s atmosphere, from where they then come hurtling down at these incredible speeds.

Unlike the more common ballistic missiles, which travel in a fairly predictable arc – a parabolic curve – hypersonic glide vehicles can move in an erratic way, manoeuvred in final flight towards their target.

Then there are hypersonic cruise missiles, which hug terrain, trying to stay below radar to avoid detection.

They are similarly launched and accelerated using a rocket booster, then once they reach hypersonic velocity, they then activate a system known as a “scramjet engine” that takes in air as it flies, propelling it to its target.

These are “dual-use weapons”, meaning their warhead can be either nuclear or conventional high explosive. But there is more to these weapons than speed alone.

More from InDepth

For a missile to be classed as truly “hypersonic” in military terms, it needs to be manoeuvrable in flight. In other words, the army that fired it needs it to be able to change course in sudden and unpredictable ways, even as it is hurtling towards its target at extreme speeds.

This can make it extremely hard to intercept. Most terrestrial-based radars cannot be relied upon to detect hypersonic missiles until late in the weapon’s flight.

“By flying under the radar horizon they can evade early detection and may only appear on sensors in their terminal flight phase, limiting interception opportunities,” says Patrycja Bazylczyk, research associate at the Missile Defence Project at the Centre for Strategic and International Studies in Washington DC, which has received some of its funding from US government entities, as well as defence industry companies and others.

The answer to this, she believes, is bolstering the West’s space-based sensors, which would overcome the limitations of radars on the ground.

AFP via Getty Images

AFP via Getty ImagesIn a real-time war scenario, there is also a terrifying question facing the nation being targeted: is this a nuclear attack or a conventional one?

“Hypersonics haven’t so much changed the nature of warfare as altered the timeframes within which you can operate,” says Tom Sharpe, a former Royal Navy Commander and anti-air warfare specialist.

“The basics of needing to track your enemy, fire at them, then manoeuvre the missile late on to allow for a moving target (the great advantage of ships) are no different from previous missiles, be that ballistic, supersonic or subsonic.

“Similarly the defender’s requirement to track and either jam or destroy an incoming hypersonic missile are the same as before, you just have less time”.

There are signs that this technology is worrying Washington. A report published in February this year by the US Congressional Research Service warns: “US defence officials have stated that both terrestrial and current space-based sensor architectures are insufficient to detect and track hypersonic weapons.”

Yet some experts believe that some of the hype around hypersonics is overdone.

Is the hype overdone?

Dr Sidharth Kaushal, from the Royal United Services Institute defence think tank, is among those who think that they are not necessarily a gamechanger.

“The speed and manoeuvrability makes them attractive against high value targets and their kinetic energy on impact also makes them a useful means of engaging hardened and buried targets, which might have been difficult to destroy with most conventionally armed munitions previously.”

But though they travel at five times the speed of sound or more, there are measures to defend against them – some of which are “effective,” argues Mr Sharpe.

The first is making tracking and detection more difficult. “Ships can go to great lengths to protect their position,” he adds.

“The grainy satellite picture available from commercial satellites only needs to be a few minutes out of date for it to be of no use for targeting.

“Getting satellite targeting solutions current and accurate enough to use for targeting is both difficult and expensive.”

But he points out that artificial intelligence and other emerging technologies will likely change this over time.

Caution around the Russia threat

The fact remains that Russia and China have stolen a march when it comes to developing these weapons. “I think the Chinese hypersonic programmes… are impressive and concerning,” says Mr Freer.

But he adds: “When it comes to the Russians, we should probably be a lot more cautious about what they claim.”

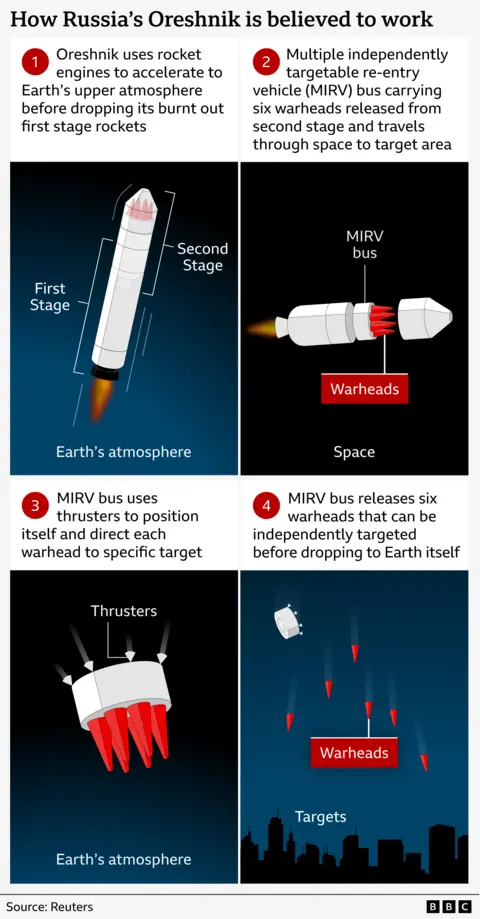

In November 2024, Russia launched an experimental intermediate-range ballistic missile at an industrial site in Dnipro, Ukraine, using it as a live testing ground.

The missile, which Ukraine said travelled at hypersonic speeds of Mach 11 (or 8,439mph), was given the name ‘Oreshnik’, Russian for hazel tree.

President Vladimir Putin said that the weapon travelled at a speed of Mach 10.

Its warhead is reported to have deliberately fragmented during its final descent into several, independently targeted inert projectiles, a methodology dating back to the Cold War.

Someone who heard it land told me that it was not particularly loud but there were several impacts: six warheads dropped at separate targets but as they were inert, the damage was not significantly greater than that caused by Russia’s nightly bombardment of Ukraine’s cities.

For Europe, the latent threat to Nato countries comes primarily from Russia’s missiles, some of which are stationed on the Baltic coast in Russia’s exclave of Kaliningrad. What if Putin were to order a strike on Kyiv with an Oreshnik, this time armed with a full payload of high explosive?

The Russian leader claimed this weapon was going into mass production and that they had the capacity, he said, to turn targets “to dust”.

Russia also has other missiles that travel at hypersonic speeds.

Putin made much of his air force’s Kinzhal (Dagger) missiles, claiming they travelled so fast it was impossible to intercept. Since then, he has fired plenty of them at Ukraine — but it turns out that the Kinzhal may not be truly hypersonic, and many have been intercepted.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesOf concern to the West is Russia’s super-fast and highly manoeuvrable Avangard. At a ceremony for its unveiling in 2018 – along with five other so-called ‘superweapons’ – Putin declared it was unstoppable.

Dr Sidharth Kaushal suggests its primary role may actually be “overcoming US missile defences”.

“Russia’s state armament programmes also suggest its production capacity for a system like Avangard is limited,” he argues.

Elsewhere, as the contest for strategic supremacy in the Western Pacific heats up between the US and China, the proliferation of China’s ballistic missile arsenal poses a serious potential threat to the US naval presence in the South China Sea and beyond.

China has the world’s most powerful arsenal of hypersonics. In late 2024, China unveiled its latest hypersonic glide vehicle, the GDF-600. With a 1,200kg payload, it can carry sub-munitions and reach speeds of Mach 7 (5,370mph).

‘Milestone moment’ in the UK’s rush to catch up

The UK is behind in this race, especially as it’s one of the five nuclear-armed permanent members of the UN Security Council. But belatedly, it is making an effort to catch up, or at least to join the race.

In April, the Ministry of Defence and the Defence Science and Technology Laboratory announced that UK scientists had reached “a landmark moment” after the successful completion of a major testing programme.

The UK’s propulsion test was the result of a three-way collaboration between the UK government, industry and the US government. Over a period of six weeks a total of 233 “successful static test runs” were carried out at the NASA Langley Research Centre in Virginia, USA.

John Healey, the UK’s Defence Secretary, called it “a milestone moment.”

But it will still be years before this weapon is ready.

REUTERS/Valentyn Ogirenko

REUTERS/Valentyn OgirenkoAs well as creating hypersonic missiles, the West should focus on creating strong defence against them, argues Mr Freer.

“When it comes to missile warfare, it’s all about two sides of the same coin. You’ve got to be able to do damage limitation while also having the ability to go after the enemy’s launch platforms.

“If you’ve got both hands available, and you can both defend yourself to an extent and also counter attack… then an adversary is a lot less likely to attempt to initiate conflict.”

However, Tom Sharpe is still cautions about the extent to which we should be concerned at the moment.

“The key point with hypersonics,” he says, “is that both sides of this equation are as difficult as each other – and neither are perfected… yet”.

Top image credit: EPA/KCNA – a treated image of what is claimed to be the successful test firing of a North Korean hypersonic missile

BBC InDepth is the home on the website and app for the best analysis, with fresh perspectives that challenge assumptions and deep reporting on the biggest issues of the day. And we showcase thought-provoking content from across BBC Sounds and iPlayer too. You can send us your feedback on the InDepth section by clicking on the button below.