Trump promised retribution – how far will he go?

36 minutes ago

Anthony ZurcherNorth America correspondent

Anthony ZurcherNorth America correspondent

BBC

BBCDonald Trump swept back into the White House this year promising, among other things, retribution against his perceived enemies. Nine months later, the unprecedented scope of that pledge – or threat – is fully taking shape.

He has vocally encouraged his attorney general to target political opponents. He has suggested the goverment should revoke TV licences to bring a biased mainstream media to heel. He has targeted law firms he sees as adversaries, pulling government security clearances and contracts.

Trump’s moves have been conducted with the kind of open zeal – brazenness, his critics say – that might belie how dramatic and norm-shattering they are.

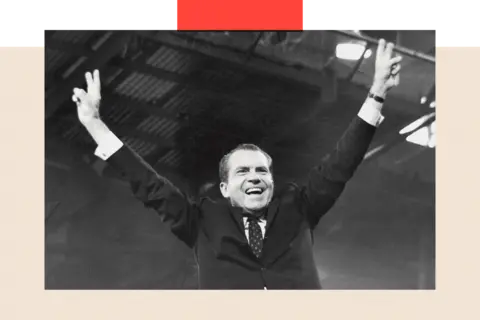

His demand a week ago that the Justice Department prosecute a handful of named political opponents, for instance, is the kind of thing that, when it was discussed in private and revealed in Oval Office recordings a half-century ago, prompted a bipartisan outcry that led to Richard Nixon’s resignation as president.

Now it is just a blip in the weekly news cycle. And the pace at which Trump is expanding presidential authority in order to impose his will is if anything accelerating.

On Thursday, Trump signed an order on “domestic terrorism and political violence”, saying it would be used to investigate “wealthy people” who fund “professional anarchists and agitators”. He suggested liberal billionaires George Soros and LinkedIn founder Reid Hoffman could be among them.

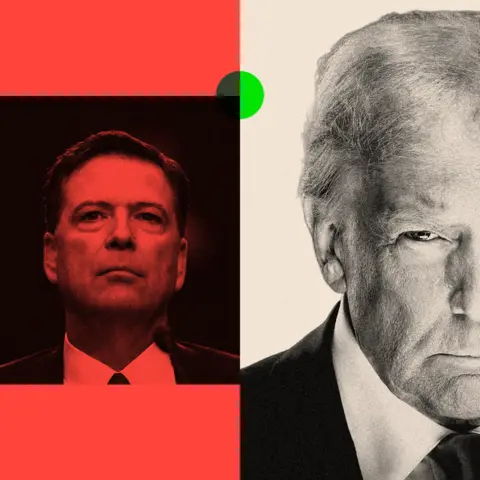

Then hours later, Trump’s Justice Department announced it had indicted James Comey, the former FBI director and Trump critic whom the president had said was “guilty as hell” days earlier.

Getty

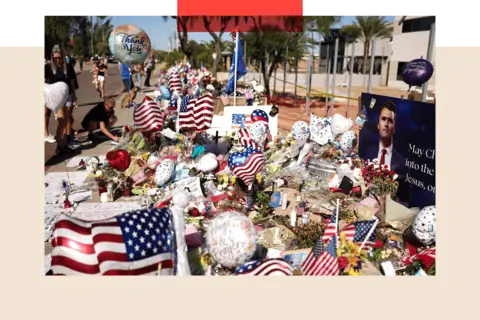

GettyTrump has justified a looming crackdown on left-wing groups by pointing to two recent, and shocking, acts of violence. First, the killing of conservative activist Charlie Kirk on a college campus, and then this week’s gun attack targeting immigration agents in Dallas, in which two migrant detainees were wounded and one killed.

The president says his broader blitz of action is necessary, and urgent. The investigations of political opponents, he says, are about targeting law-breakers and members of the “deep state” who undermined his first presidential term. The mainstream media, in the view of his Maga coalition, should be held to account over alleged bias and “fake news”. Private businesses weakened by diversity policies and political corruption require the firm hand of government to set them straight.

He and his supporters also accuse the Biden administration of being the real culprit behind any presidential norm-breaking.

During the Democrat’s four years in office, Trump was indicted four times and convicted once. Several of his close aides – including fomer 2016 campaign chair Steve Bannon and trade adviser Peter Navarro – were prosecuted and imprisoned for contempt of Congress. Others were indicted for their alleged role in attempting to overturn the 2020 presidential election.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe Biden White House directed social media companies to restrict what it characterised as harmful speech during the Covid pandemic. And the president attempted to expand presidential powers to implement his agenda, including student loan forgiveness, vaccine mandates, protection of transgender rights in public schools and environmental regulation.

Turnabout, Trump’s side might say, is fair play – but the differences between the Biden actions and those being undertaken by this president are at times stark.

While Trump was prosecuted, only two of the cases were brought by the federal government and both by a special prosecutor set up to be independent of Biden’s justice department. Biden, unlike Trump, remained largely silent about the cases. Many of Biden’s executive actions were undone by the Supreme Court, which so far has given Trump a free hand to operate.

Such details may be of lesser concern to Trump, however, who has portrayed himself as a persecuted figure – and used this sense of grievance to connect with many of his voters, who share a similar sense of injustice at an establishment they view as tilted against them. And Trump may feel less restrained in his second term given that, last year, the Supreme Court held that US presidents, including Trump, are largely free from criminal liability for official actions they take.

A tale of two presidents

Underlying the entirety of the debate about presidential power and “retribution” has been a fundamental disagreement between Biden and Trump over the nature of the existential dangers facing America and the world.

The core belief among many in the top ranks of Trump’s White House is that America – and Western civilisation writ large – face a dire threat from leftist culture, mass migration, unbalanced global trade and intrusive government.

During a fiery speech on Sunday at the memorial service for slain conservative activist Charlie Kirk, longtime Trump adviser Stephen Miller – the architect of Trump’s immigration policies and one of his most vocal defenders – said that America’s legacy “hails back to Athens, to Rome, to Philadelphia, to Monticello”.

“You have no idea how determined we will be to save this civilisation,” he said. “To save the West, to save this republic.”

CHARLY TRIBALLEAU/AFP via Getty Image

CHARLY TRIBALLEAU/AFP via Getty ImageThis kind of outlook stands in sharp contrast to the one outlined by Biden during his presidential term. In his view, the defining fight of the era was not between Western civilisation and forces that would destroy it, but between democratic and authoritarian nations.

“We’re at an inflection point between those who argue that autocracy is the best way forward and those who understand that democracy is essential,” Biden said in 2021. “We must demonstrate that democracies can still deliver for our people in this changing world.”

Now, Trump’s critics say, the current president is more than just abandoning that fight. In their view, he is pushing the US towards authoritarianism.

How the US political landscape changed

The Comey indictment, for those who believe Trump is an aspiring autocrat, is only the latest example of this president targeting critics based on a sense of personal grievance and retribution.

In the days before Comey was charged with making a false statement to Congress and obstructing justice, Trump called on Attorney General Pam Bondi to prosecute not just the former FBI director but also New York Attorney General Letitia James and California Senator Adam Schiff – figures he has accused of conspiring against him.

“We can’t delay any longer, it’s killing our reputation and credibility,” he wrote. “They impeached me twice, and indicted me (5 times!), OVER NOTHING. JUSTICE MUST BE SERVED, NOW!!!”

Reuters

ReutersThe federal prosecutor who had been investigating Comey and James resigned amid the pressure, and was replaced by a former personal lawyer to Trump. She is reported to have personally presented the Comey case to the grand jury – a panel of citizens who assess the strength of the case – that indicted him.

“This is unprecedented, to have the president basically direct his people to indict a specific individual because he’s angry at that person,” Laurie Levenson, a law professor at Loyola Marymount University, told the BBC.

Other prominent critics of the president have also faced investigations. In August, federal agents raided the home and office of John Bolton, a former Trump national security adviser turned sharp critic, as part of an inquiry into his handling of classified documents. John Brennan, head of the CIA during the Obama presidency, is reportedly also under investigation.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesPresident Trump has also waged a campaign against major media outlets, which he has said are overwhelmingly critical of him in violation of federal law. He has sued the New York Times and Wall Street Journal for billions of dollars, after settling suits with both ABC News and CBS News.

Last week, even some high-profile Republicans cried foul after Brendan Carr, the head of the Federal Communications Commission, successfully urged local stations to drop one of America’s biggest late-night comedy shows over comments host Jimmy Kimmel had made about Charlie Kirk, his suspected killer and the way Trump had mourned him.

The president then doubled down, saying networks that give him “bad publicity” should perhaps be targeted.

Amid the furore, Texas Senator Ted Cruz compared Carr’s threats against media companies to mob tactics, while his colleague Rand Paul of Kentucky called them “absolutely inappropriate”.

Some on the left go much further, however, drawing dark comparisons to 1930s Germany. “Trump is the Hitler of our time,” was one of the chants protesters lobbed against the president when he dined with aides at a Washington restaurant last month.

“Anyone who thinks we’re on the way to authoritarianism is wrong,” Democratic Senator Chris Van Hollen of Maryland said this week. “We’re already there.”

The Trump administration says such warnings are not only unfounded but hysterical – the manifestation of “Trump derangement syndrome”. They draw a direct line between such criticism and recents acts of violence, including the killing of Kirk.

“If you want to stop political violence, stop telling your supporters that everybody who disagrees with you is a Nazi,” Vice-President JD Vance said this week.

Reuters

ReutersThe concept of “democratic backsliding” and whether it’s happening in the United States, however, does not have to rely on fraught debates referencing the rise of 20th Century fascism.

The Varieties of Democracy Institute based at the University of Gothenburg in Sweden conducts an annual survey of the state of government around the globe. It found that 72 percent of the world’s population now lives in autocracies – the highest level since 1978.

In 2024, 45 countries were moving toward more autocratic government across the globe, including in places like Hungary, Turkey, Mexico, Greece and Ghana.

In these nations, the patterns were similar – erosions in freedom of speech, open elections, the rule of law, judicial independence, civil society and academic freedom.

Governments expanded their power over institutions and individuals. It didn’t happen in the same order or at the same speed, but in the end the destination was the same.

According to the institute, the US has been demonstrating similar “concerning” trends – trends they say are moving at a pace unprecedented in modern American history.

EPA

EPA“The expansion of executive power, undermining of Congress’ power of the purse, offensives on independent and counter-veiling institutions and the media, as well as purging and dismantling of state institutions – classic strategies of autocratisers – seem to be in action,” its latest report, released in March, found.

“The enabling silence among critics fearful of retributions is already prevalent.”

‘I am your retribution’

At a March 2023 rally in Waco, Texas, Trump was beginning to find his footing in his bid to win back the White House. A week earlier, he had publicly speculated that he was on the verge of being indicted in New York for fraud over hush-money payments to former porn star Stormy Daniels before the 2016 election. Those charges, for which Trump would ultimately be convicted, were filed five days later.

On that sweltering afternoon before a crowd of around 15,000 loyal supporters, however, Trump delivered a series of promises.

“I am your warrior,” he said. “I am your justice. And, for those who have been wronged and betrayed, I am your retribution.”

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe concept of retribution became a common theme for Trump on the campaign trail for the next year and a half. Sometimes he would say “success” would be his retribution. Other times, such as in a series of interviews following his May 2024 felony conviction, he was more blunt.

He told television psychologist Dr Phil that “sometimes revenge can be justified” and “revenge does take time”. And in answering a question about retribution posed by Fox News’s Sean Hannity, he said that he had every right to “go after” Democrats “based on what they have done”.

On Friday, Trump said the indictment of Comey was “about justice, not about revenge” but added that he expected “others” would follow.

“This is also about the fact that you can’t let this go on,” he told a pack of reporters at the White House. “They are sick, radical-left people and you can’t let them get away with it.”

More from InDepth

BBC InDepth is the home on the website and app for the best analysis, with fresh perspectives that challenge assumptions and deep reporting on the biggest issues of the day. And we showcase thought-provoking content from across BBC Sounds and iPlayer too. You can send us your feedback on the InDepth section by clicking on the button below.