Ukrainians would like to watch comedies – but for now their culture is defined by war

56 minutes agoSarah RainsfordSouthern and Eastern Europe correspondent, in Kyiv

BBC

BBCI’ve never heard an audience so silent.

When the credits rolled on a screening of 2000 metres to Andriivka, no-one in the Kyiv cinema moved. Their popcorn and beer were mostly untouched.

The documentary by Mstyslav Chernov is a frontline film so intense you feel like you’re trapped in the terrifying trenches alongside the soldiers.

Watching that in Ukraine, a country under fire, the intensity is multiplied.

At the start of Russia’s full-scale invasion in 2022, as society mobilised to defend itself, Ukraine had little capacity for culture. Venues were closed or repurposed, some were attacked, and artists became refugees or soldiers.

Almost four years on, the arts are back – but everything is now permeated by the war.

Global Images Ukraine

Global Images UkraineThe change struck me on a recent trip to Kyiv.

I realised that city walls were plastered with two kinds of poster: fundraisers for forces on the frontline – or films, plays and exhibitions about the war.

Andriivka wasn’t the only hard hitting film on offer: there were also ads for Kuba and Alyaska, another powerful documentary that follows two female combat medics in a way that manages to be funny, frightening and tragic at the same time.

There was unflinching photography, too.

The old Lenin Museum, now Ukrainian House, was hosting a giant retrospective of the work of documentary photographer Oleksandr Glyadelov.

Stretched over three floors of the spiralling modernist building, his images captured the span of Ukraine’s struggle for independence: 35 years trying to wrest itself from Russian control.

In the section devoted to 2022 and beyond, he’d displayed his photos of victims’ bodies on the ground to look like graves.

Some I talked to in Kyiv shy away from all of this.

War is their reality: it’s what keeps them up at night, with the air defence guns and missile warnings. It’s all over their social media feeds and it’s in their fears for friends and family who are fighting.

It is the last thing they want more of, on stage or screen.

But others are clearly drawn to it.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAndriivka is Chernov’s latest production after his film from besieged Mariupol won an Oscar.

His focus this time is a 2km-long strip of land in eastern Ukraine. The soldiers call it a forest, though it’s just a line of scraggy trees separating them from Russian positions. Their mission is to cross it and reclaim Andriivka, hanging Ukraine’s national flag on the ruins.

So the men in the trenches dart between foxholes, guided by soldiers in the rear who monitor from drones and warn of any threat they see. They control the real-life troops as in a computer game but their faces are stony, their focus total.

The soldiers’ lives depend on them.

When it’s over, the audience around me seem stunned.

“Someone I know was in this movie, a soldier, and he died,” Yulia shares, when people eventually file out into the foyer.

She says it was a tough watch. “I think we have to do it, though. We can’t forget them.”

An older man openly admits he’d viewed the film through tears. “Some moments were really, really hard,” Taras says.

But he’s sure such films are necessary.

“Maybe people will realise that Ukraine needs all the help possible to end this,” Taras argues. “So many people have been killed because we refuse to be what we’re not. We are not Russian.”

It’s not only the “serious” arts tackling the war these days. Musicals, the ultimate form of escapism, are in on the act too.

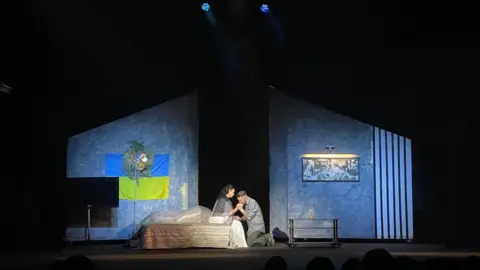

Just over the road from the cinema, I spotted a banner for the latest offering from the Kyiv Opera: Patriot, a rock opera in two acts.

“It’s the story of any one of us,” the director explains, one that takes the hero on a journey through Ukraine’s recent history – from revolution to war.

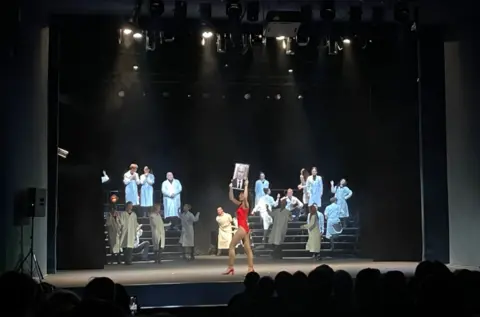

All the songs are hugely popular anthems of Ukrainian independence so the audience on premiere night whooped along, swept to their feet at times. There were cheers for the policeman on stage in a fat suit doing pelvic thrusts, and the woman in a leotard and tights shredding a portrait of Vladimir Putin.

It was all a million miles from the films watched in silence across the road.

But director Petro Kachanov told me that even musical theatre has a mission now.

“We have to do everything to demonstrate that Russia is our age-old enemy,” he was candid. “The Russians are not our brothers. They are killing our people. They want to take away our freedom and we must say this.”

His team had pressured him to give the show a happy ending for a public exhausted by four years of open war, but he refused.

“This play is a tribute to those who died in this war,” he told me. “And we cannot think about our own comfort when the best sons of Ukraine are dying.”

The same ethos is driving the current “explosion” of documentaries.

Since February 2022, TV news channels in Ukraine have towed the official line and told reassuring stories in the name of unity. But independent filmmakers zoom in on the hardship.

“People who want to know truth, they go to the cinema,” Olha Birzul is blunt.

She says that role was “born on the Maidan”, shorthand for the mass protests in 2014 that eventually swept a pro-Russian president from power.

When crowds occupied Kyiv’s main square in 2014, those who could film began recording everything. “So when the full-scale invasion happened, they were ready.”

Ultimately, the films they are producing today are heroic tales: the enemy and the cause are clear. But they also expose the harshest of realities of this war and its true cost.

Olha’s own husband was killed fighting in 2022 and, for her, such films are a way of recording Ukrainians’ sacrifice and honouring their memory.

“It’s a form of justice,” she says.

“We would really like to watch other movies – maybe some comedies or some drama,” is how one filmgoer, Natalia, put it on her way out of a screening of Kuba and Alyaska.

“Of course I don’t want to watch these movies, but I have to, like everyone else. Because it’s our history and it’s our present day.”