Universities are ‘failing us’ on mental health, say students – but should it really be up to them?

36 minutes ago

Joe McFaddenBBC News

Joe McFaddenBBC News

BBC

BBCWhen Imogen arrived at the University of Nottingham in September 2022, she carried with her a letter addressed to the student wellbeing services. As a teenager, she struggled with anxiety and self-harm. The letter, written by her former head of year, was a direct plea to the university to help her.

Three years on, Imogen (not her real name) feels let down. She has since been diagnosed with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and autism, and was referred for university counselling multiple times, but, instead of helping, she says it made her feel worse.

“I felt like I was being thrown between services, no-one wanted me and no-one could help me.”

Another student at Nottingham, Leacsaidh, who was diagnosed with obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD) at age 17, characterises the services as “one-size-fits-all”.

She says that when she sought help for self-harm, she was simply given website references.

BBC/ Guida Simoes via Getty Images

BBC/ Guida Simoes via Getty ImagesThe University of Nottingham is certainly not an outlier, nor is it considered worse than other British universities for mental health support.

Jana, an international student at King’s College London (KCL), was diagnosed with anxiety by a university GP, which made her eligible for certain adjustments, but she found the process of implementing them “painful”.

Requests for deadline extensions, she says, were delayed by clerical errors, compounding her anxiety at an already stressful time.

KCL did not respond to a request for comment.

Given that the number of young people reporting mental health concerns is rising, these sorts of issues could get worse.

Christopher Furlong, Getty Images

Christopher Furlong, Getty ImagesFor its part, the University of Nottingham says it has invested in its specialist wellbeing services in recent years.

A spokesperson says they “encourage any student with concerns to discuss their experiences with us”.

However, they also stress: “University services are there to support the mental health and wellbeing of our students but are not a replacement for clinical NHS services to treat more serious or complex needs.”

Which raises the question: are institutions really letting students down – or is the expectation placed on them part of the issue?

And to what extent should the responsibility fall on universities in the first place?

‘Prime conditions’ for problems

The extent of the crisis in student mental health came to public attention in 2018 after Natasha Abrahart, a physics student at the University of Bristol, killed herself. Ten others are believed to have taken their own lives at the university between 2016 and 2018.

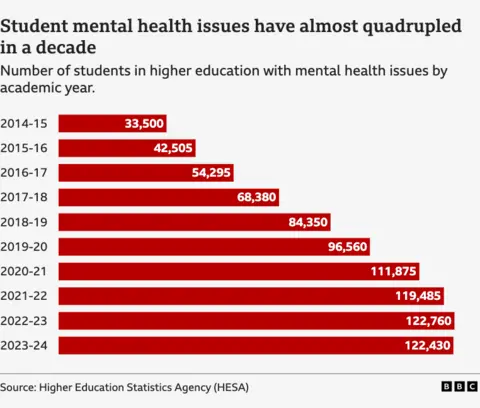

In the decade to 2023-24, the number of students with a mental health condition almost quadrupled, according to the Higher Education Statistics Agency (HESA), increasing every year to 2022-23 before dipping slightly in 2023-24.

That year, some 122,430 students in the UK (out of a total of 2.9 million) said they had a mental health condition. Most were undergraduates, and the majority were women.

Part of this may be down to age. Late adolescence (18 to 21) is what Dr Sandi Mann, a senior psychology lecturer at the University of Central Lancashire, calls the “peak ages” for many mental health problems, including OCD, anxiety and depression.

There is no recent parallel data that directly compares the mental health of young people who do not attend university or higher education.

But combining the stresses of late adolescence, academic pressure, learning how to live independently, and, for some, part-time work, creates the “prime conditions” for mental health issues, argues Dr Mann.

A lack of “resilience” also concerns her. “I’m not talking about serious mental health issues, such as severe OCD, anxiety and depression,” she says.

“Of course they need help. But young people seem to struggle more coping with the day-to-day stresses of everyday life.”

Abrahart Family

Abrahart FamilySome have argued that society is increasingly pathologising

Ben Locke, an American psychologist who researches US colleges’ support services, has argued that many mental health assessment tools cross over with normal human distress, leading to more people being told they need professional help.

But Dr Sarah Sweeney, the incoming chairwoman of the student services organisation Amosshe, and head of student support and wellbeing at Lancaster University, argues that encouraging young people to talk about mental health has removed some of the stigma.

She also believes, however, that more could be done to educate people about when something is a mental health challenge or problem. “Which is different from a diagnosed mental illness,” she stresses.

‘We’re not trained for this’

Another part of the challenge is that the first point of contact for students reporting mental health challenges is often their personal tutor – an academic.

Dr Mann stresses that a personal tutor – sometimes called an academic advisor – is not a mental health practitioner. Their main role should be signposting and sometimes referring students to counselling services.

One senior humanities lecturer at the University of Manchester, who asked not to be named, says that in their department, personal tutors are given a “handbook of academic advising” and some PowerPoint slides, which they describe as a “series of generic questions to ask” in specific situations.

Geography Images via Getty Images

Geography Images via Getty ImagesThe level of training a personal tutor is given varies between universities. But often an academic’s first indication of an issue is during casual conversations with a student about not submitting a piece of work on time.

This can mean tutors “don’t really know that [they are] intervening in a mental health crisis”, they explain. “And it’s a problem that we’re not trained for.”

They summed up the situation at universities as “grim”. “It has gone from being a really serious problem to being a really major crisis… People are swamped.”

The University of Manchester said that “all student-facing staff can access a rolling programme of training on responding to mental health difficulties in students”, run by mental health nurses, and that there are “clear and rapid” routes to escalate cases. All academic advisors receive training and have the support of an advisor network, it said.

It added that it had significantly increased investment in student health and wellbeing in the last few years.

‘People can slip through the gaps’

Some students argue the sheer number of services, and the levels of complexity around how to access it, can make it difficult to get the help they need.

Generally, after speaking to a personal tutor, the second step for a student might be to meet with a wellbeing team, which may help them take steps to “manage stress and the transition to university”, including advice on topics like good sleep and managing anxiety.

Wellbeing advisers will typically assess whether a student’s case needs escalating, and might refer students for specialist support like disability services or counselling through the university’s in-house team.

Students who are seriously unwell – or those who may be a risk to themselves or others – are escalated to a final step. This usually means making contact with the local health authorities about managing risk.

Dr Sweeney says this can all be “a lot” to get your head around.

More from InDepth

“Even as a mental health professional it’s really difficult to navigate,” adds Dr Mann. “Nobody really knows who to go to.”

There is, at both universities and mental health services more widely, a “real danger that people can slip through the gaps”.

Universities are spending more on these services: their spend increased by 73% on average in the past five years, according to research of 72 UK universities by Times Radio and The Sunday Times released in January. This is despite almost half of universities expecting to be in financial deficit this summer, according to the Office for Students.

“Student services can do a lot, but it needs to be properly resourced, and there is increasing demand,” says Dr Sweeney.

“We could be part of the whole drive to streamline… but you have to resource those services properly for them to be effective.”

What role should universities play?

Some academics argue it is not a university’s job to look after students like a school teacher would. Another lecturer at Manchester, who prefers not to be named, argues that: “Students are adults, they are over 18 when they are coming to university”.

However, they concede that it is “very hard on a human level” to just turn students away.

Dr Sweeney similarly emphasises that universities are not mental illness treatment centres. (Indeed, student services will always tell a student in serious crisis or immediate stress to seek help from their GP or NHS services.)

But some students are put off by long NHS waiting times, including for mental health services.

Abrahart Family

Abrahart FamilyOne argument is that universities need closer collaboration with NHS authorities to improve mental health care.

In Manchester, local authorities have created a scheme called the Greater Manchester Universities Mental Health Service, under which local universities, including the University of Manchester, can escalate a case meaning authorities respond faster.

Dr Sweeney says the scheme is currently working well. But she acknowledges that it is new, and relies on local NHS services having the capacity.

However, others believe universities need to take on more responsibility. Natasha Abrahart’s father Bob is one of them.

“If universities can’t provide a safe and supportive environment then they are not fit for purpose,” he argues.

The duty of care debate

Natasha was just 20 when she took her own life on the day of an assessed presentation. Natasha – who had a diagnosed social anxiety disorder – became distressed at the prospect of having to deliver the oral assessment to a full lecture theatre.

In May 2022, Bob, together with Natasha’s mother Maggie, sued the university. Bristol County Court found it had breached its obligations under the Equality Act to make “reasonable adjustments” to the way Natasha was assessed, and ordered the university to pay more than £50,000 in damages.

The University of Bristol has not responded to a request for a comment.

Student suicide rates are believed to be lower than the general population. The Office for National Statistics (ONS) estimates that 319 students died by suicide between the 2016-17 and 2019-20 academic years.

However it stresses that there is no central database recording student suicides – instead, they cross-referenced death certificates with student records to identify potential cases of student suicides.

In May, a report by the National Confidential Inquiry into Suicide and Safety in Mental Health (NCISH) at the University of Manchester concluded universities needed to do more to prevent student suicides, including mandatory mental health awareness and suicide prevention training for staff.

Bob and Maggie are calling on the government to introduce a statutory duty of care in higher education, or a legal obligation to protect students from harm.

The court in Bristol found there was no “statute or precedent” establishing this duty of care.

Andrew Aitchison via Getty Images

Andrew Aitchison via Getty ImagesThe Department for Education says it has no plans to introduce this because higher education providers already owe “a duty of care to not cause harm to their students through the university’s own actions”.

Both Amosshe and Universities UK, which represents university vice-chancellors, oppose the change too. Amosshe says it would “place unrealistic expectations over what higher education providers can control”.

Yet most universities acknowledge something must change.

Dr Sweeney says the sector could be doing more, as there is not a standardised student services model across higher education. But she also adds university is a “more supportive environment than the workplace”.

Meanwhile Dr Mann believes that it is about giving students the “scaffolding” to thrive. “They’re used to adults just stepping in and rescuing them. I think we need to teach them to rescue themselves.”

As for the students, many I spoke to say they still feel let down. “I wish,” says Imogen, “I could say everything was great and I had a really supportive uni. But I can’t.”

Support and information for anyone affected by the issues raised in this article can be found on the BBC Action Line website.

Top image credit: Jodi Lai, BBC

BBC InDepth is the home on the website and app for the best analysis, with fresh perspectives that challenge assumptions and deep reporting on the biggest issues of the day. And we showcase thought-provoking content from across BBC Sounds and iPlayer too. You can send us your feedback on the InDepth section by clicking on the button below.