What are the government’s planned welfare cuts and how much will they save?

13 minutes agoBen ChuBBC Verify

Getty Images

Getty ImagesA significant number of Labour MPs are threatening to vote against the government’s working-age welfare reform plan when it comes before the House of Commons next week.

The reforms are designed to reduce the overall working-age welfare bill by about £5bn a year by the end of the decade.

The rebel MPs have signed an amendment to the legislation that makes a series of objections, including a lack of official consultation and impact assessments.

BBC Verify explains the detail of the reforms and their possible impact.

Which benefits would be cut?

The government wants to save money by:

- making it harder for people to access Personal Independence Payments (Pip)

- cutting the rate of incapacity benefit

Incapacity benefit – which is mainly paid through the health element of Universal Credit – goes to those deemed to be unable to work for health reasons.

This benefit is set to be reduced by 50% in cash terms for new claimants from April 2026. For existing claimants, it is due to be held flat in cash terms until 2029-30 – meaning payments will not rise in line with inflation.

The government estimates these two changes will save £3bn a year by the end of the decade.

Pip is paid to people with a long-term physical or mental health condition or a disability and who need support. Work and Pensions Secretary Liz Kendall has acknowledged that almost 20% of recipients are in work.

The government plans to make it more difficult for people to claim the “daily living” element of Pip from 2026-27.

Under the current assessment system, claimants are scored on a zero to 12 scale by a health professional on everyday tasks such as washing, getting dressed and preparing food.

Under the proposed change, people would need to score at least four on one task, ruling out people with lower scores who would previously have qualified for the benefit.

The government estimates this will save an additional £4.5bn a year from the welfare bill by the end of the decade.

Why is the government trying to cut welfare spending?

It is concerned about the rise in the number of people claiming working-age benefits in recent years and the implications of this trend for the public finances.

Last Autumn, the government projected that the numbers of working-age claimants of Pip in England, Scotland and Wales would rise from 2.7 million in 2023-24 to 4.3 million in 2029-30, an increase of 1.6 million.

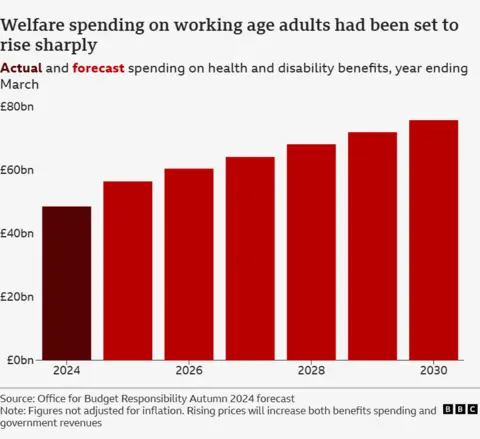

At that time, the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR), the government’s official forecaster, projected that the overall cost of the working-age benefit system would rise from £48.5bn in 2024 to £75.7bn by 2030.

That would have represented an increase from 1.7% of the size of the UK economy to 2.2%, roughly the size of current spending on defence.

Ministers argue that this rising bill needs to be brought under control and that changes to the welfare system are part of that effort.

It is worth noting though that – even after factoring in the planned cuts – the OBR still projected this bill to continue to rise in cash terms to £72.3bn by 2030.

And the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) still projected the total number of working-age Pip recipients to rise by 1.2 million between 2023-24 and 2029-30 – after the cuts.

In this sense, the main effect of the Pip cuts would be to reduce the increase in claimants that would otherwise have occurred.

What would the impact of the reforms be?

The government’s official impact assessment estimates that about 250,000 additional people (including 50,000 children) will be left in “relative poverty” (after housing costs) by 2030 because of the reforms.

However, that assessment included the impact of the government deciding not to proceed with welfare reforms planned by the previous Conservative administration, which government analysts had judged would have pushed an additional 150,000 people into poverty.

Some charities and research organisations have suggested this means the government’s 250,000 estimate understates the impact of its own reforms, since the previous administration’s reforms were never actually implemented.

Iain Porter from the Joseph Rowntree Foundation has suggested the actual poverty impact of the government’s changes could therefore be up to 400,000 (adding the 250,000 figure to the 150,000 figure to generate an estimate of the total numbers affected).

However, the government’s impact assessment cautions against simply adding the two figures together, noting that “some people are affected by more than one [reform] measure”, meaning this approach risks double counting individuals.

Taking account of this, the Resolution Foundation think tank has estimated that the net effect of the government’s reforms would mean “at least 300,000” people entering relative poverty by 2030.

What about the impact on employment?

The government has claimed that its reforms are not just about saving money, but helping people into work.

Chancellor Rachel Reeves told Sky News in March 2025 that: “I am absolutely certain that our reforms, instead of pushing people into poverty, are going to get people into work. And we know that if you move from welfare into work, you are much less likely to be in poverty.”

To this end, the government is gradually increasing the standard allowance in Universal Credit – the basic sum paid to cover recipients’ living costs – by £5 a week by 2029-30.

This is projected to be a net benefit to 3.8 million households and the government argues it will also increase the incentives for people to work rather than claim incapacity benefits.

The government is also investing an extra £1bn a year by 2029-30 in additional support to get people out of inactivity and into employment.

What are the rebels’ objections?

The rebel MPs say disabled people have not been consulted on the proposed reforms.

They also say there has been no evaluation of the overall employment impacts by the OBR.

It is true that the government has not consulted disabled people on the specific cuts to Pip and incapacity benefits, though it is now consulting on the broader reform package.

It is also the case that the OBR has not yet done a full employment impact assessment, though the forecaster says it will do one before the Autumn Budget.

Meanwhile, the Resolution Foundation has done its own estimate of the employment impact of the overall reform package.

It estimates the total increase in employment could be between 60,000 and 105,000, although it stressed that these figures are highly uncertain.

This positive employment figure contrasts with the 800,000 people who are projected to lose part of their Pip payments by 2029-30 and the 3 million people families who will see a cut in their incapacity benefits.