What the NHS can learn from the European country that boosted cancer survival rates

1 hour ago

Hugh PymHealth editor

Hugh PymHealth editor

BBC

BBCJesper Fisker, chief executive of the Danish Cancer Society, is looking back 25 years – to the moment Denmark decided to transform its approach to treating cancer.

At that point, he says, the country did not have a strong record.

“It was a disaster,” he recalls. “We saw Danish patients out of their own pocket paying for tickets to China to get all sorts of treatments – endangering their health.”

Some went to private hospitals in Germany that offered new treatments unavailable in Denmark.

Back then, Denmark’s record on cancer was low compared to that of other rich countries. But so was the UK’s.

From 1995 to 1999, Denmark’s five-year survival rate for rectal cancer was essentially tied with the UK’s, on around 48%, according to the International Cancer Benchmarking Partnership, a research body. It put both nations well below countries like Australia, which had a 59% rate.

Now, thanks to a bold plan, Denmark’s performance on cancer has jumped ahead. By 2014, its five-year survival rate for rectal cancer had risen to 69%, close to Australia’s. (The UK’s rose too, but only to 62%.)

Analysts think the trend has probably continued (though these are the most up-to-date figures available). And it’s a similar story for other cancers, including colon, stomach, and lung.

This Danish success story has caught the attention of UK policymakers. Health Secretary Wes Streeting says that aspects of the Danish model are feeding into government plans.

Some could well be included in a new long-term cancer plan for England, due to be published in the autumn.

So, what’s their secret, and can the NHS learn from Denmark?

Big investments and thoughtful touches

Walking today into Herlev Hospital on the outskirts of Copenhagen makes for a rather different experience to arriving at an average NHS hospital.

The foyer is hung with bright, vivid paintings by the Danish artist Poul Gernes. There are 65 in all.

The philosophy is that endless white walls can unnerve patients, while colour can be a pleasant distraction from their problems.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIt is a sign of the attention Denmark has paid to even the atmosphere of hospitals – small, thoughtful touches, alongside investment in more traditional equipment.

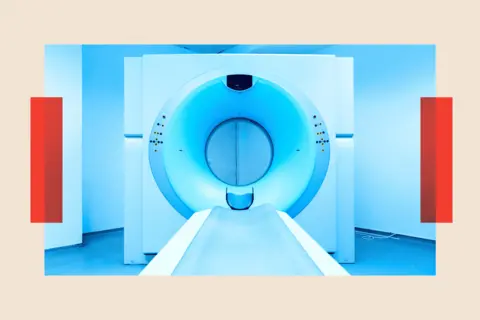

Dr Michael Andersen, a consultant radiologist and associate professor at the hospital, shows off a high-tech scanner, only the fourth of its kind used by any hospital around the world.

Buying hospital equipment like this – particularly scanners – has been central to Denmark’s cancer strategy.

“In 2008 the government made the decision to make a heavy investment into scanner systems,” Dr Andersen explains. “They purchased between 30 and 60 – they’re an integral part of the way we work.”

Particularly important for cancer are CT scanners, which look deep inside a person’s body. Denmark now has about 30 of them per million people – the average of other rich countries stands at 25.9.

The UK, meanwhile, lags way behind with just 8.8 scanners per million people, according to the 2021 figures.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe investment in cancer equipment, according to experts, led to a huge expansion in diagnostic capacity in Denmark. Unless funding to meet increasing patient demand is made, they argue, England could continue to lag behind on the quality of care.

This all comes despite the fact that Denmark’s health spending hasn’t seen a huge boost.

Calculated by spending per head of the population, Denmark is ahead; but as a share of national income, its health spending is similar to, and in fact slightly below that of the UK’s.

A bold set of plans

This is just one part of a bold plan drawn up by Danish health leaders. Along with introducing new equipment, and rethinking the atmosphere of hospitals, they also made it possible for patients to be treated with chemotherapy at home.

New national standards govern how quickly Danes must be treated: following a referral, a cancer diagnosis has to be given within two weeks. Then, if treatment is required, it has to start within the two weeks of diagnosis.

If these targets are not met patients have the right to transfer to another hospital – or, failing that, another country – whilst still being funded by the Danish health system.

This is quite a contrast to the UK nations. Here, the target is for patients to start treatment within around nine weeks (officially, 62 days) of an urgent cancer referral.

Getty Creative

Getty CreativeMichelle Mitchell, chief executive of Cancer Research UK, believes that there is a lack of accountability in the English health system specifically, with too many NHS organisations. Addressing this, she says, should improve the quality of cancer care.

“That means clarity over who in the government and NHS is responsible for delivering each part of the plan.

“Ultimately, responsibility for the success or failure of the plan should rest with the health and social care secretary.”

She points out that there are similarities between England and Denmark’s state-run health systems – for example, the roughly similar amount they spend on health as a share of national income, meaning Denmark’s example could be followed in England.

But this would require a long-term plan, political leadership, higher investment, more cancer screening, and stronger targets. Which is no easy feat.

Going beyond just ‘treating’ cancer

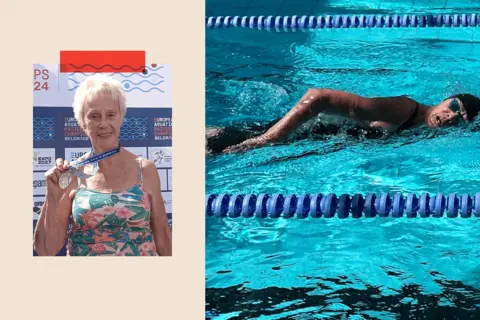

Elisabeth Ketelsen, who is 82, is an active person, still swimming in international events – she has broken world records for her age group. But in 2022, she discovered a lump in her breast.

“I saw the doctor on Monday – on the following Thursday I had mammography and a biopsy and from then on it went so quickly my head was spinning, almost.”

Elisabeth Ketelsen

Elisabeth KetelsenJust three weeks after the diagnosis Elisabeth, who is from Denmark, had surgery. Radiotherapy started two weeks later.

Last year, the cancer reappeared in her spine and she was immediately prescribed chemotherapy pills and hormone treatment. The cancer stabilised and she has come off chemotherapy.

She has since returned to the swimming pool, competing at an event in Singapore.

“The system works,” she tells me.

Not all Danish patients are as complimentary, of course, but Danish health officials say their targets for rapid cancer diagnosis are being met for about 80% of their patients.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThis all comes down to the idea that Danish authorities are not just trying to treat cancer; they’re also keen to improve the experience of patients.

Counselling houses, where therapy and companionship are offered to patients, have opened up across the country. These are funded largely by the voluntary sector with a small amount of state funding. (These follow a similar model as the Maggie’s cancer support charity in the UK.)

Mette Engel, who runs a counselling centre in Copenhagen, tells me mental health is very important in Denmark’s cancer plan.

“We see ourselves as a national part of this support system.”

Benefits of chemotherapy at home

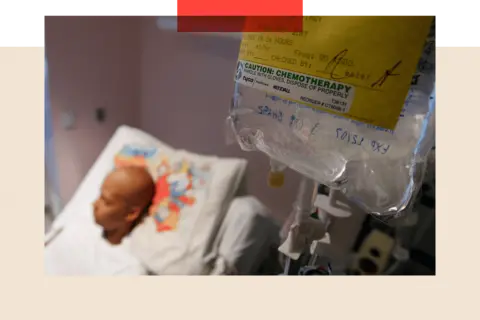

Denmark’s move to start treating more cancer patients away from hospitals is also part of this wider shift of Danish healthcare from hospitals into communities.

Michael Ziegler, mayor of Høje-Taastrup Municipality near Copenhagen, was diagnosed with leukaemia in 2022. After a stem cell transplant, he was back at work within seven months.

Ziegler had chemotherapy in his own home, using what’s known as a chemo pump.

“I could have some quality of life, being able to do things at home I wanted to do instead of being stuck in a hospital room,” he says.

“I also think at hospitals there is always at risk of getting infections. The chemo has the effect of reducing my immune system to a very low level so I am vulnerable to infections.”

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThere haven’t yet been any major studies and so hard data is limited, but it’s thought by some that at-home chemo could potentially boost survival chances by lowering the risk of a patient catching an infection while in hospital.

His cancer has since returned and he will be restarting treatment, including more chemotherapy and a new stem cell transplant.

He says he is “feeling optimistic”.

A blueprint for the NHS?

The Danish health system has certain parallels with the NHS – not least as both are mainly funded by taxpayers.

The two nations also face similar challenges when considering the overall health of the population. Alcohol consumption is similar in both nations, though obesity levels in Denmark are lower and smoking rates are higher. (One Danish health leader told me that they were envious of UK initiatives on smoking, with the minimum age for tobacco sales rising each year.)

However, there are certain challenges specific to the UK: the population of England, for example, is nearly 10 times larger than Denmark’s population. And the NHS is a complex organisation.

Still, ministers have made no secret of their interest in the Danish system, with an official visit earlier this year.

Wes Streeting, the UK Health Secretary, says: “Denmark’s healthcare system is known the world over for its excellence, having transformed outcomes through its cancer plans, and Health Minister Karin Smyth’s trip to the country earlier this year offered us vital insights up close.”

Mr Streeting says these insights have “fed into” government health plans to “speed up cancer diagnoses and deliver cutting edge treatments to the NHS front line quicker”.

Michelle Mitchell of Cancer Research UK agrees that Denmark offers a useful template. “They are diagnosing cancer earlier, people are surviving longer, more people are taking up screening – all of those factors as well as investment in workforce and kit are critical components of a cancer plan.”

She argues that British health ministers could move towards Danish-style national waiting time targets rather than the UK’s current system of “benchmarks”, which are weaker and haven’t been met since 2015.

‘This is unfinished business’

The greater challenge for the NHS though, is that there are so many other problems – crowded A&E departments, overstretched staff and, as one analyst put it, “multiple fires burning” – meaning that it can be difficult to persuade health leaders to focus on cancer survival.

Ruth Thorlby, assistant director of policy at The Health Foundation think tank, says that policymakers in London and Copenhagen both realised at the same time, in the 1990s, that cancer needed urgent attention and urgent plans were drawn up.

But whilst Danish policymakers saw policies through, she argues that in the UK the momentum “dissipated”, as other priorities and short-term problems emerged.

“This is unfinished business – over the last decade there has been a move away from cancer plans,” she says.

PA Wire

PA WireAt the heart of Denmark’s success was a sense of political consensus. From the 1990s onwards, figures from all major parties agreed that cancer should be a priority. This is a level of agreement the UK has not managed to reach, she says.

Mr Fisker of the Danish Cancer Society argues that the usual cut-and-thrust of party politics needs to be set aside. “Politicians must promise each other there is going to be a long, lasting partnership. And health leaders need to operate on a 10-, 15-, 20-year basis,” he says – longer than the life of any one government or party.

But does he think that’s possible in the UK? After all, Westminster is not known for much long-term, cross-party thinking.

“If you are really decisive, if you really want to do this and are committed to it over a period of time, and you are also ready to invest then I think it can be done,” he says.

With a pause, he adds: “Nothing comes without investment.”

More from BBC InDepth

BBC InDepth is the home on the website and app for the best analysis, with fresh perspectives that challenge assumptions and deep reporting on the biggest issues of the day. And we showcase thought-provoking content from across BBC Sounds and iPlayer too. You can send us your feedback on the InDepth section by clicking on the button below.